| |

January 24, 2025

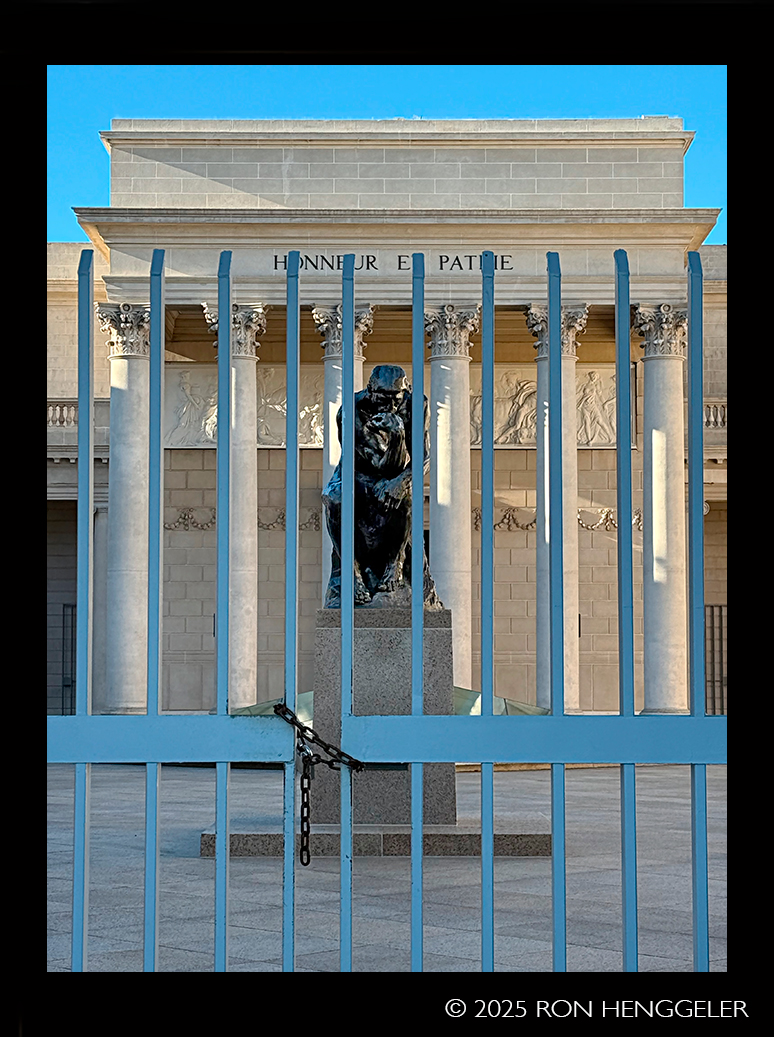

Photos from Mary Cassatt at Work

at the Legion of Honor |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) was the most celebrated woman artist of her time: a bold modernist pioneer; a committed member of the French Impressionist movement; a fiercely professional, aesthetically radical painter, pastelist, and printmaker.

Credits:

All of the text that accompanies the photos in this newsletter is respectfully copied from the walls at the museum. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

MARY CASSATT AT WORK

Mary Cassatt at Work delves into the artist's processes and materials, exploring the daring, iterative approach she used to give form to her ideas. Over fifty years of activity, she produced approximately 380 pastels, 320 paintings, and 215 print compositions. No photographs documenting her studios or procedures survive. To understand how she worked, the exhibition relies on her own words and the evidence provided by her. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

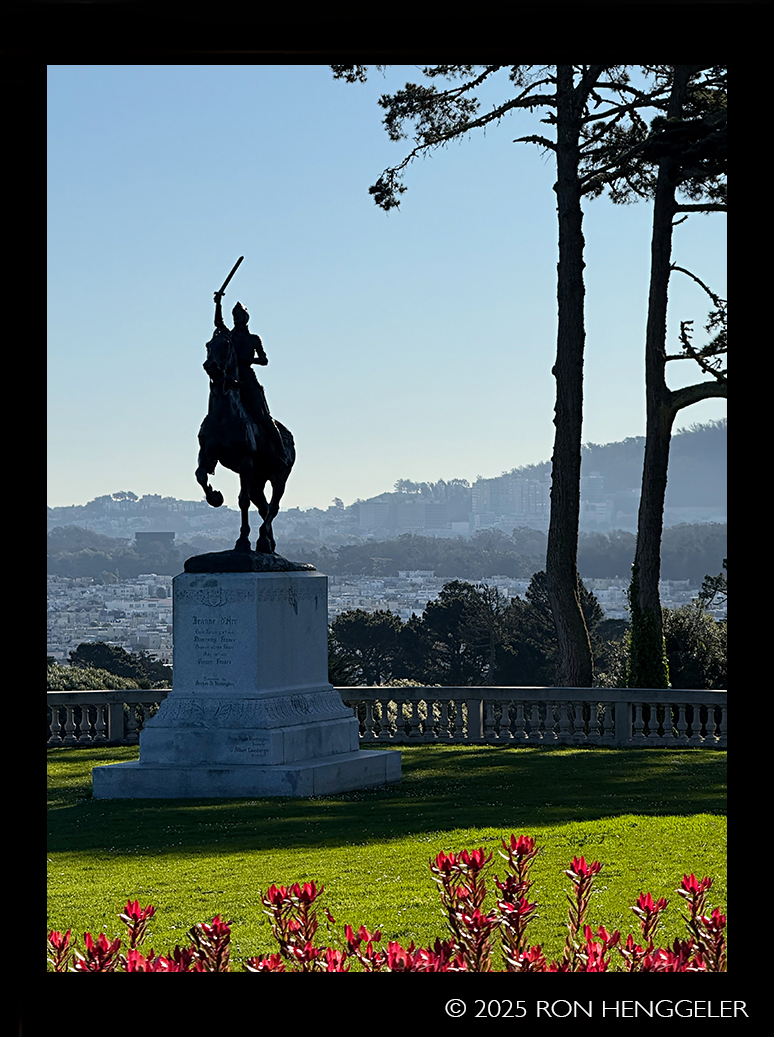

by Anna Vaughn Hyatt Huntington |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Notions of hard work and independence shaped Cassatt's life. Born into an affluent Pennsylvania family in the mid-nineteenth century, she aspired to the kind of professional artistic career then rarely open to women. Living and working most of her adult life in France, she made a name for herself picturing the active lives of upper-middle-class Parisian women, their children, and their domestic employees.

Cassatt's production in every medium is characterized by repetition and reworking, a process of ceaseless experimentation and change.

Smuggling a radical aesthetic program under cover of acceptably

"feminine" subject matter, she produced images of "women's work"-knitting and needlepoint, bathing children, nursing infants-that also testify to the work of the woman who made them: the marks of her brush, etching needle, pastel stick, and even fingertips. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Too often dismissed as a sentimental painter of mothers and children, Mary Cassatt (1844–1926) was in fact a modernist pioneer. Her paintings, pastels, and prints are characterized by restless experimentation and change. Cassatt was the only American to join the French Impressionists, first exhibiting with the group at Degas’s invitation in 1879, and quickly emerged as a key member of the movement.

Text from the museum's web site. |

|

|

| |

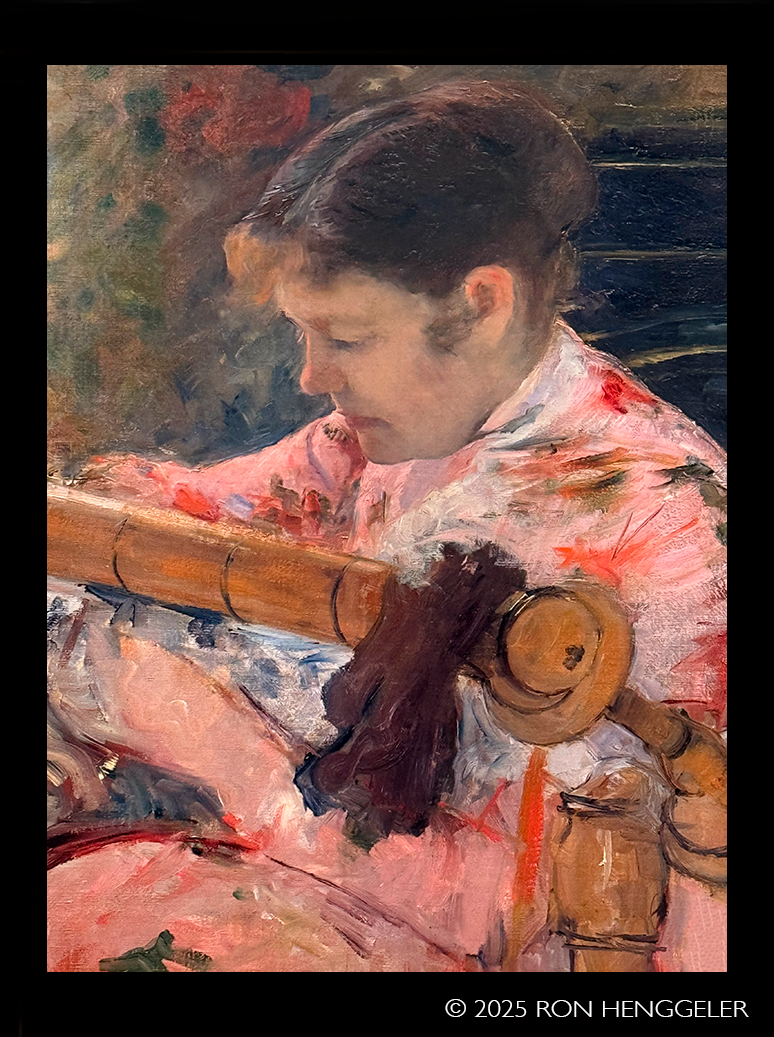

Lydia at a Tapestry Frame, ca. 1881

Oil on canvas

Lydia Cassatt (1837-1882) was her younger sister's sometime roommate and a favorite model. Here she appears intent on a piece of needlework, stretched taut beside a window. A lower-than-usual vantage calls attention to the underside of the tapestry frame, centering the animated strokes of paint that make up Lydia's nimble fingers and dangling threads. These, of course, are evidence of Cassatt's parallel work with a paintbrush, inviting us to consider the shared moment of creation: two sisters, seated across from one another, each absorbed in the work of her own hands.

Collection of the Flint Institute of Arts, Flint, Michigan, Gift of The Whiting Foundation, FIA 1967.32 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Lydia at a Tapestry Frame, ca. 1881

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

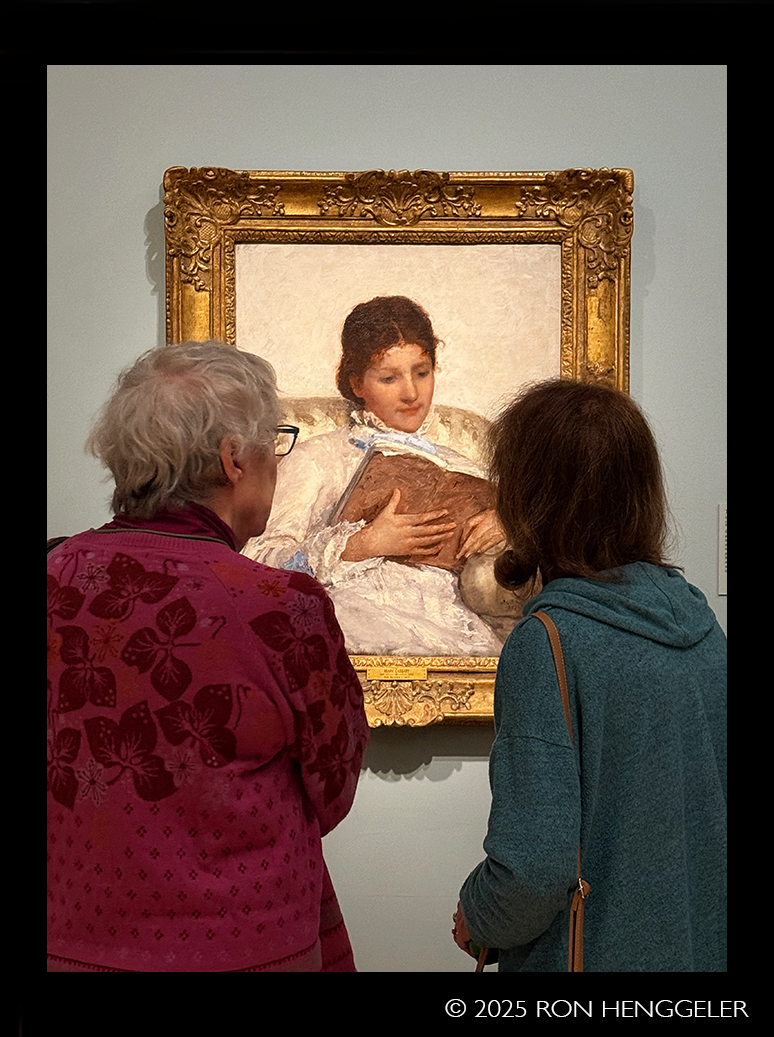

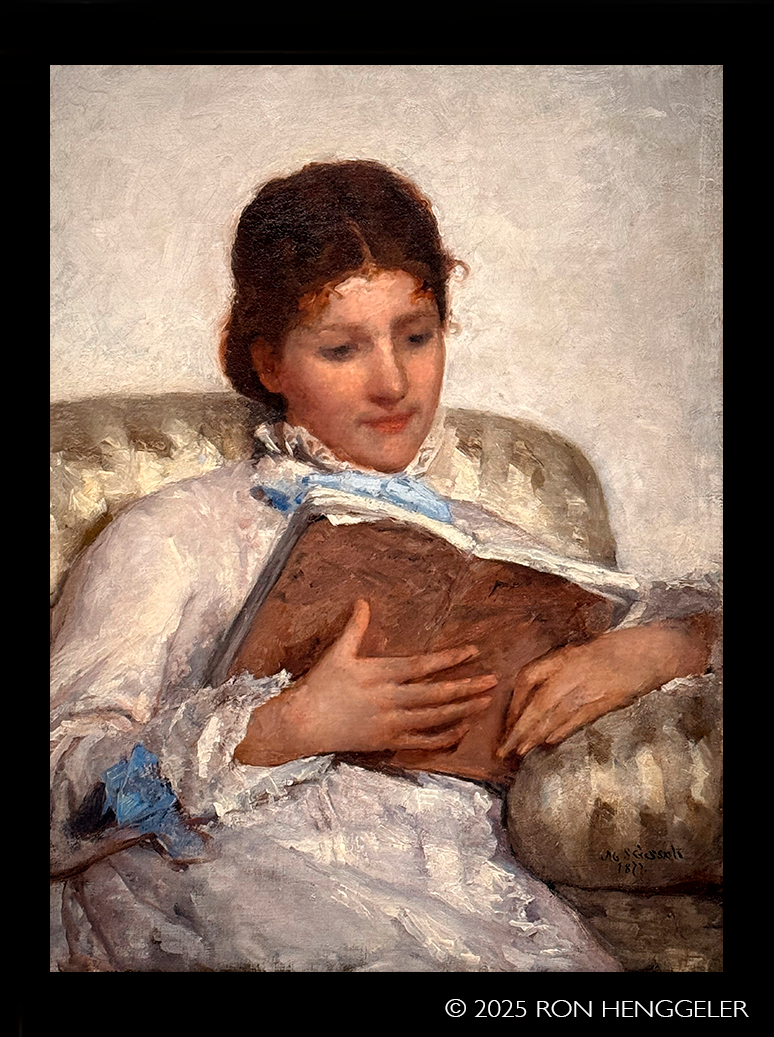

The Reader, 1877

Oil on canvas

Dating from the moment when Cassatt's artistic practice began to part ways with her academic training, this painting shows early signs of her new direction. Seen from a distance, it appears relatively conventional, in keeping with works she had previously exhibited at the annual state-sponsored Salon exhibition, but, when examined close-up, its rough, brushy surface betrays a new interest in the varied textures that could be achieved through more experimental paint handling.

Courtesy Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

IMPRESSIONISM:

PICTURING WOMEN

Cassatt's ambition to become a professional artist faced strong social and familial headwinds. As the youngest daughter in an upper-middle-class family, she was expected to marry. In her thirties, when it became apparent that she was intent on developing her artistic career, her father insisted that her studio pay for itself, a condition that spurred her to exhibit and sell her art in an increasingly modern, global, and competitive marketplace.

To achieve this goal, Cassatt found common cause with the self-styled indépendants (the independents, today known as the Impressionists), a group of artists- including Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, Auguste Renoir, and Camille Pissarro-who broke with the institutions of the French art world to pioneer new approaches, evoking scenes from modern life, often in brisk strokes of bright, unblended color.

Cassatt exhibited with the Impressionists for the first time in 1879, making a vivid debut in paint and pastel. She would later remark of her first showing with the Impressionists, "At last I could work with absolute independence." An array of theater images on view in this gallery demonstrates this sense of freedom, exemplified in a fluid movement between media, as she carried ideas and compositions from one technique into another.

As an affluent single woman and a foreigner in France-Cassatt negotiated social expectations with care. Parisian society was highly stratified and class-conscious, presenting constraints on whom and what a genteel woman artist should depict. In the face of these real-ities, she gave sustained and subtle attention to women of her own set: their social lives, intellectual habits, and especially their handwork, including knitting, sewing, and needlepoint. Though quick to distinguish her own activity from these amateur pursuits, she took the state of concentration that they required seriously as an artistic subject. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

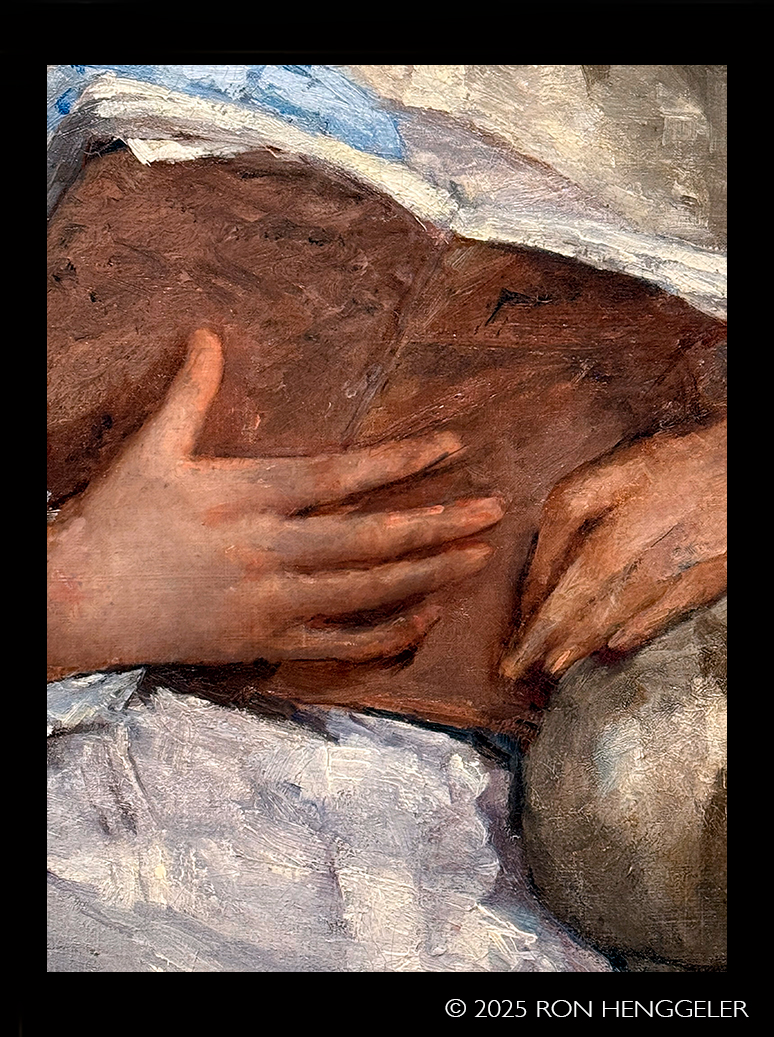

Detail of:

The Reader, 1877

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

The Reader, 1877

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

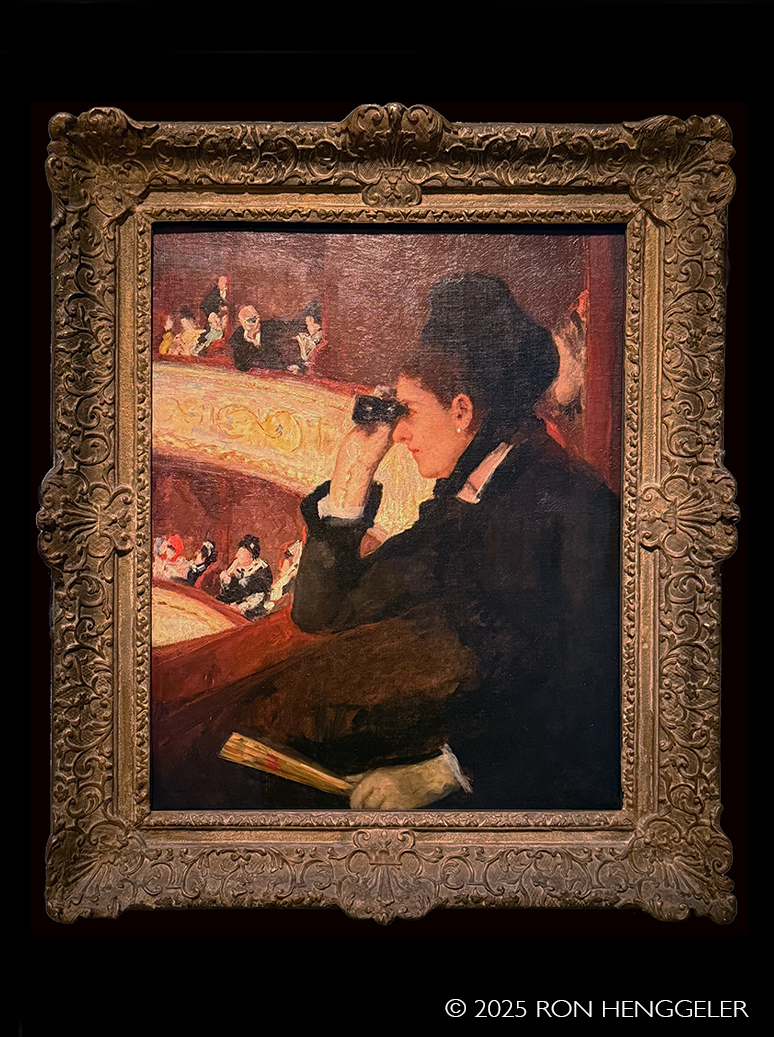

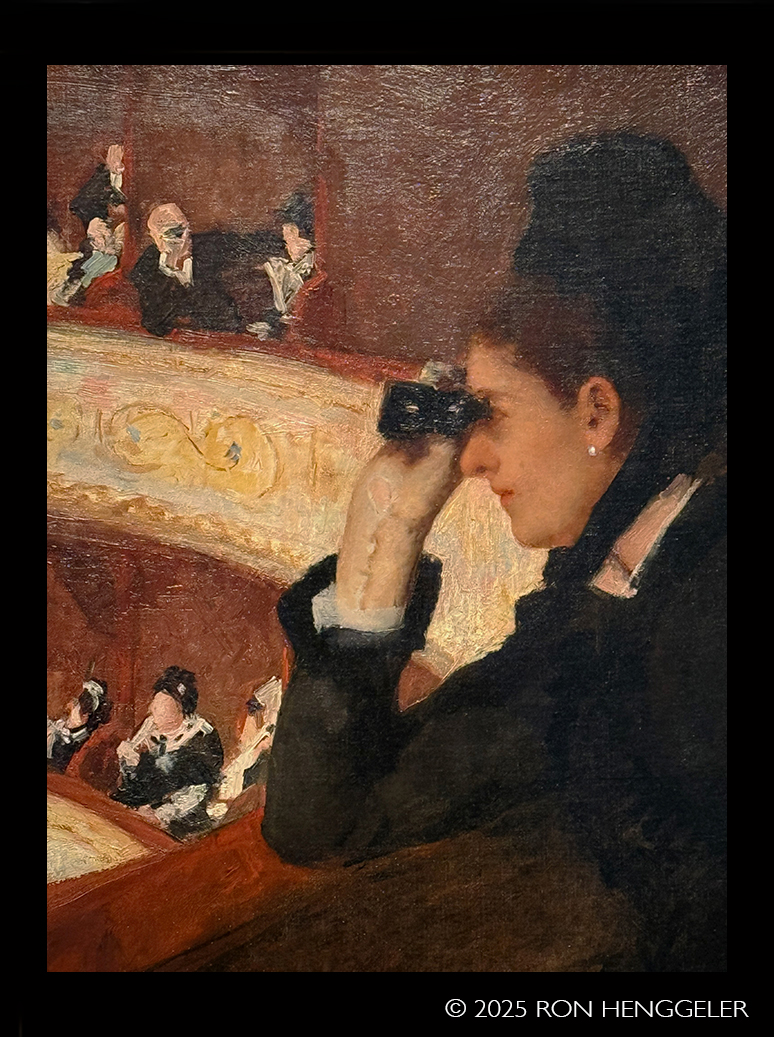

In the Loge, 1878

Oil on canvas

Cassatt joined the Impressionists at the invitation of Edgar Degas, who became a friend and collab-orator. By the end of the 1870s, Degas's images of women dancing onstage at the Paris opera were already famous. Cassatt's decision to depict genteel audience members instead responded both to the very different expectations placed on an artist of her gender and to her personal interest in portraying states of attention. Here an elegant audience member surveys the stage (or perhaps the occupant of another box seat), ignoring a fellow audience member who trains his opera glasses on her.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The Hayden Collection-Charles Henry Hayden Fund

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

In the Loge, 1878

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

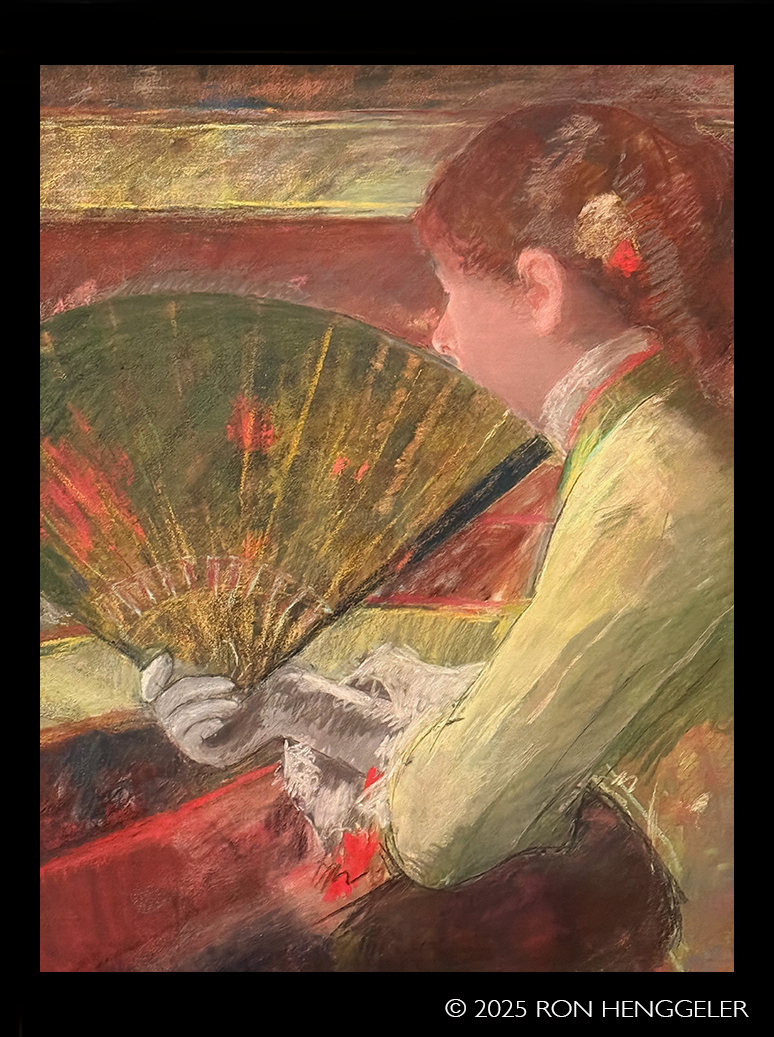

At the Theater, ca. 1879

Pastel with gold metallic paint on canvas

This pastel was one of seven works that Cassatt exhibited, in a room of her own, at her debut with the Impressionists. The material properties of pastel-its powderiness and luminosity, its ability to be layered with other media-allowed Cassatt to achieve specific textures, seen in the velvet-lined opera box and matte, papery fan in this com-position. The overall effect is more subtle and atmospheric than that of Cassatt's related depictions in oil paint, whose gloss lends itself to hard, glittering surfaces.

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. Sargent McKean, 1950 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

At the Theater, ca. 1879

Pastel with gold metallic paint on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

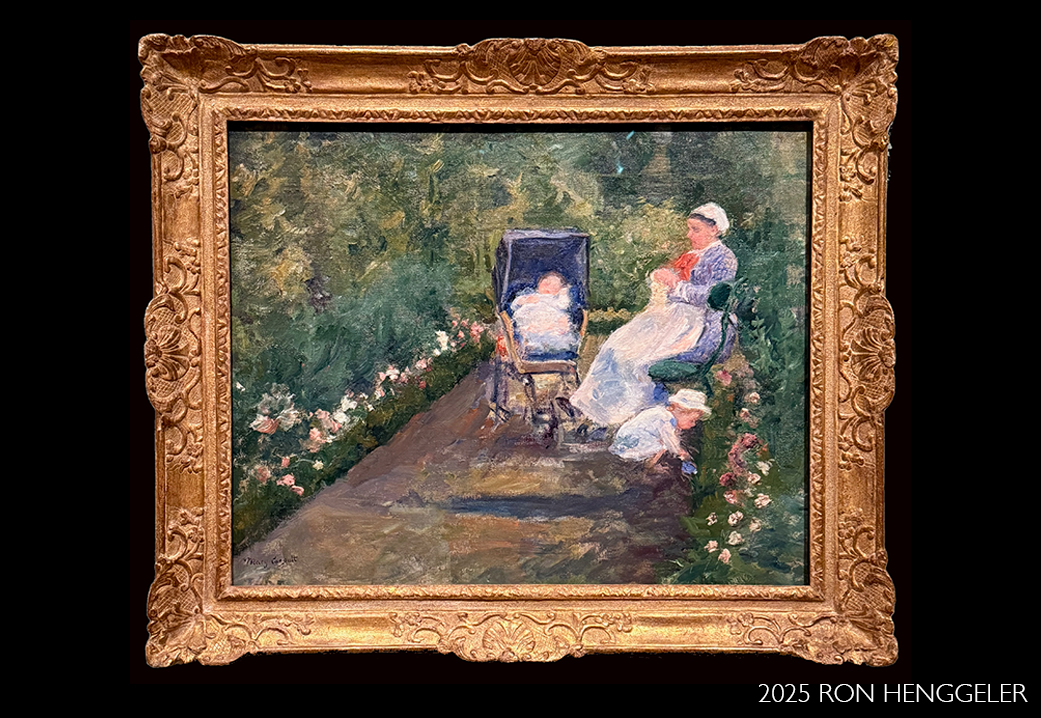

Children in a Garden (The Nurse), 1878

Oil on canvas

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston,

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Meredith J. Long, 2001.471

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Children in a Garden (The Nurse), 1878

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

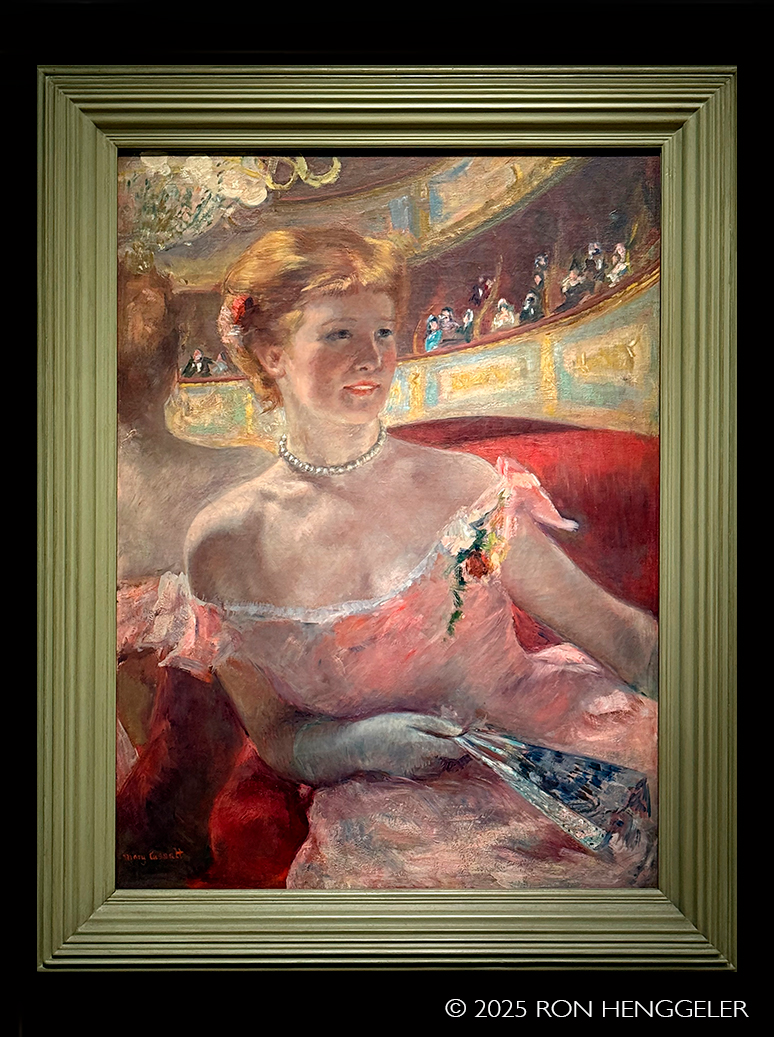

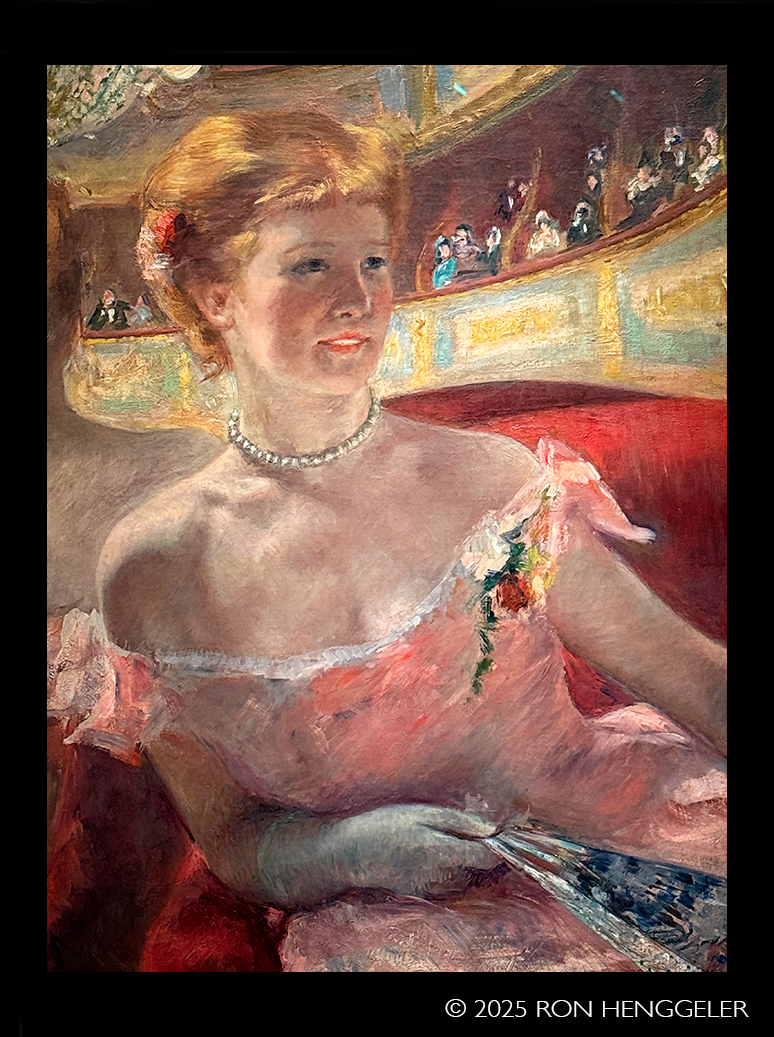

Woman in a Loge, 1879

Oil on canvas

Shown at the 1879 Impressionist exhibition, this picture places us in a Parisian theater, where Cassatt's textured application of oil paint captures the sparkle and buzz of the audience under bright illumination. Critics at the exhibition praised Cassatt's clever placement of her model before a mirror (note the blurred reflection of other audience members) but ridiculed the picture's original green frame. Cassatt intended its clean lines and color to complement her pungent reds and pinks, but reviewers found the effect garish and modern.

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Bequest of Charlotte Dorrance Wright, 1978 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Woman in a Loge, 1879

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

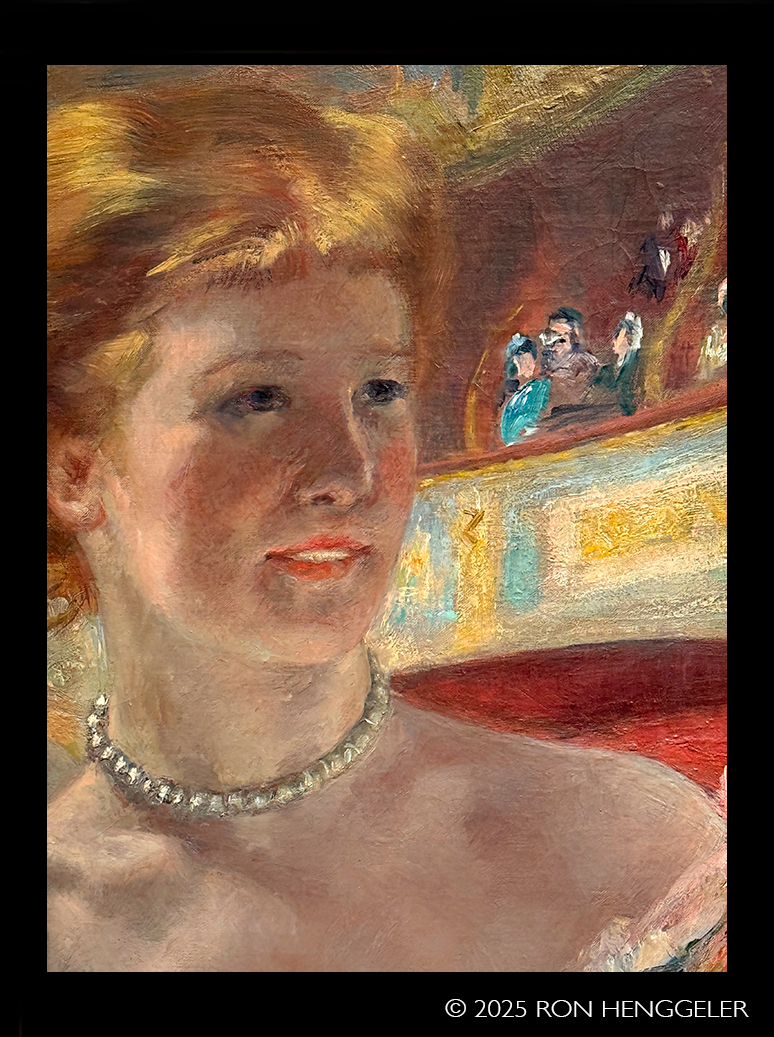

Detail of:

Woman in a Loge, 1879

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

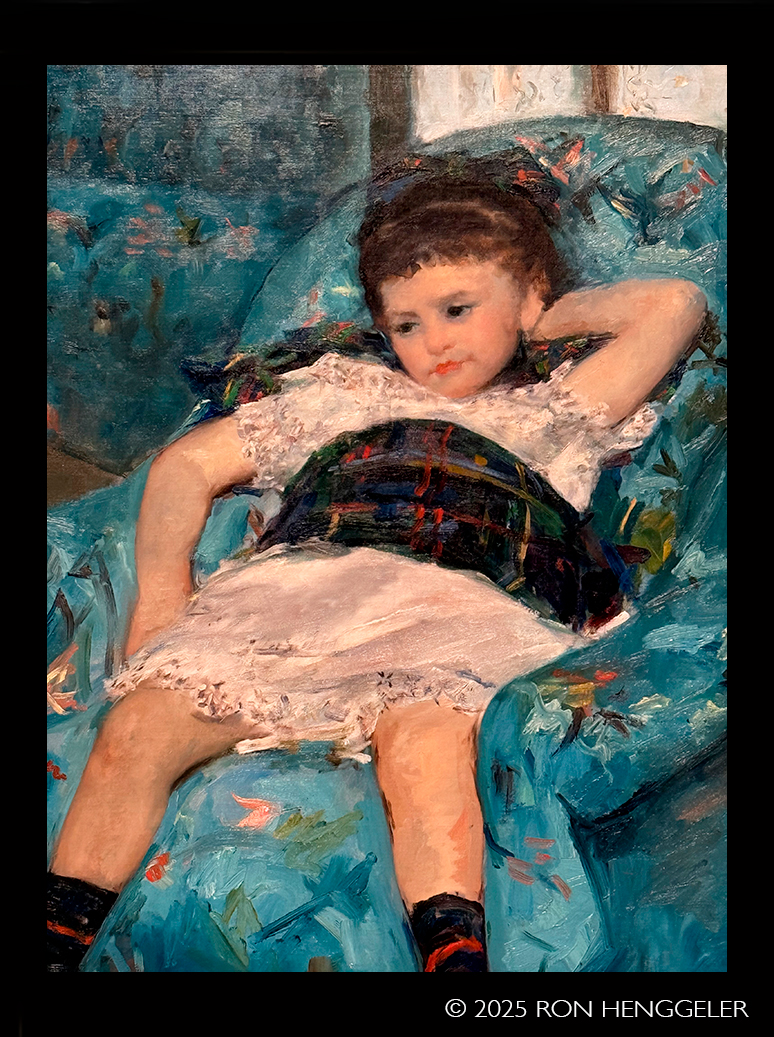

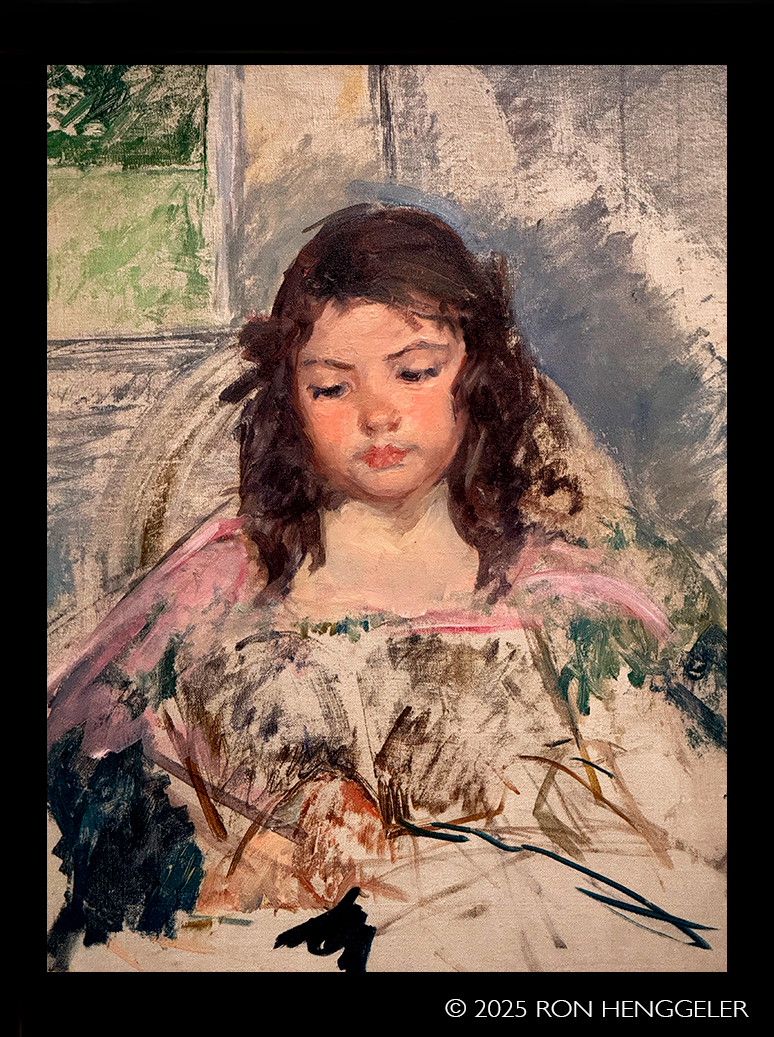

Little Girl in a Blue Armchair, 1878

Oil on canvas

Cassatt collaborated closely with Edgar Degas in the late 1870s-nowhere more closely than in this picture, which portrays the daughter of his friend in a setting heavily reworked by Degas. Cassatt submitted it to the American section of the 1878 Exposition Universelle in Paris, where it was rejected, doubtless on account of both Cassatt's free paint handling and her depiction of the young model-slumped and disheveled, with petticoats in unseemly evidence. Frustrated by the rejection, the artist vindicated the picture by exhibiting it in her Impressionist debut the following spring.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1983.1.18 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Little Girl in a Blue Armchair, 1878

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

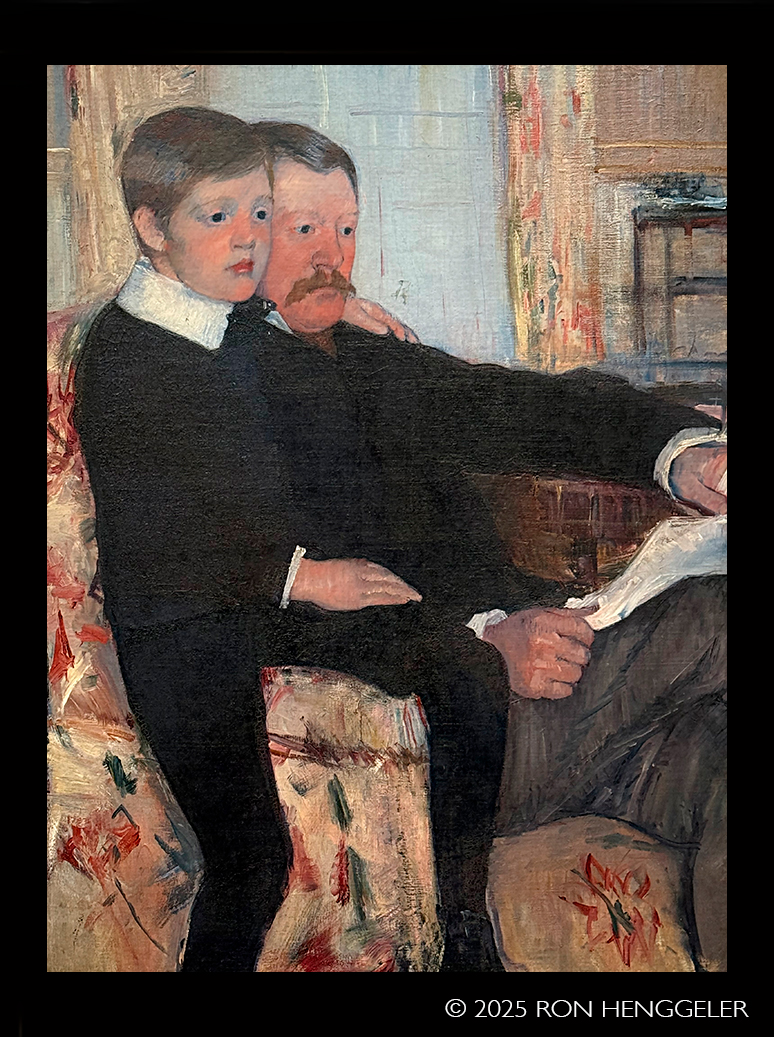

Portrait of Alexander J. Cassatt and His Son Robert Kelso Cassatt, 1884

Oil on canvas

Cassatt's brother Alexander and her eleven-year-old nephew Robert made a surprise trip to Paris in December 1884. Taking advantage of the visit, Cassatt made this rare paternal scene. While acknowledging their facial similarities and fused form, she

distinguished the blue sheen of Robert's suit from his father's brown jacket. Her brother proved a patient model, but Cassatt had to capture Robert swiftly, since he was "wriggling about like a flea."

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Purchased with the W. P. Wilstach Fund and with funds contributed by Mrs. William Coxe Wright, 1959 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

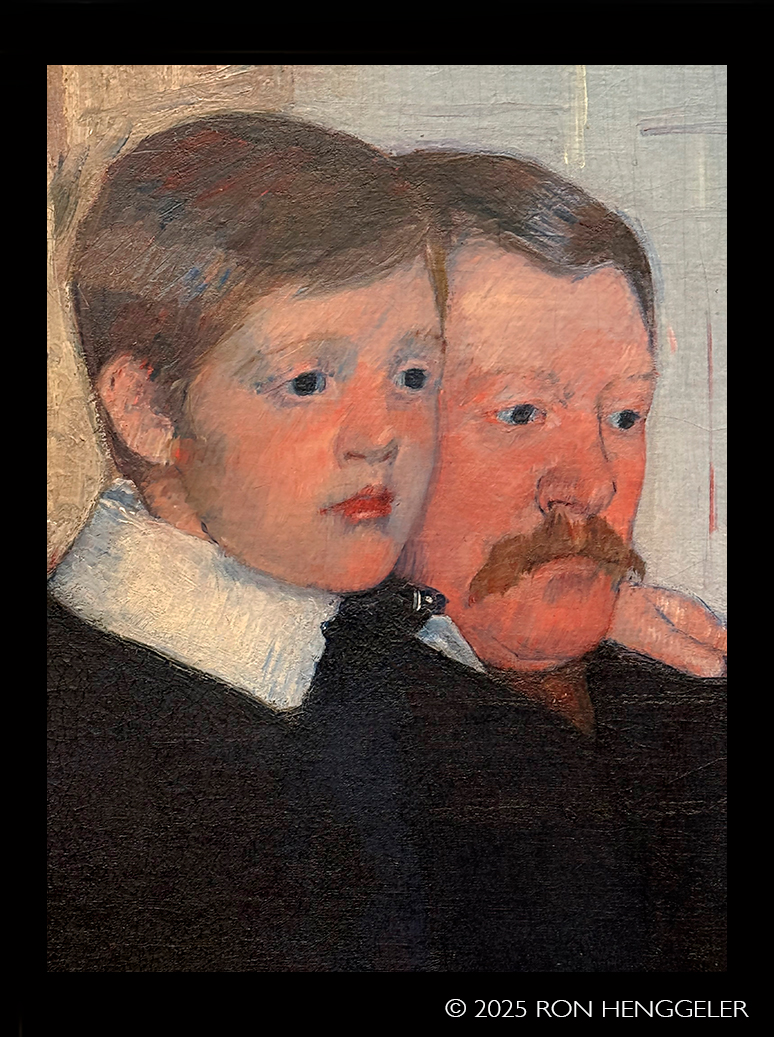

Detail of:

Portrait of Alexander J. Cassatt and His Son Robert Kelso Cassatt, 1884

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Portrait of Alexander J. Cassatt and His Son Robert Kelso Cassatt, 1884

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

CHILDREN AND CHILDCARE

Cassatt herself had no children. Her professional ambitions were incompatible with family life for a woman of her time and social class. As an artist, though, she took a keen interest in children, seeking to capture their inner lives and their intimacy with the women who cared for them.

Cassatt began with her own nieces and nephews and the children of her friends, eventually filling her studio with toys to keep her young models occupied while she painted them. By 1890, she had established an international reputation-and a budding market-for her depictions of childhood and childcare.

Cassatt's alertness to the effort involved in cuddling, breastfeeding, bathing, dressing, educating, and cajoling young children comes through in many of these scenes, making the physical and psychological work involved in childcare meaningfully visible for the first time in Western art. The reassuring "femininity" of Cassatt's subject matter, however, has tended to obscure its radical newness-matched by her equally new and radical approach to the work of art-making: the experiments with color and line that give form to her famous images of women and children. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Driving, 1881

Oil on canvas

This tightly cropped composition portrays Cassatt's sister Lydia seated beside Odile Fèvre, the niece of Edgar Degas, a close friend as well as an Impressionist colleague. Relegating the coachman to the back seat and taking the reins, Lydia seems to steer the family carriage through a Parisian park, while the little girl beside her sits stiff as a china doll. Fèvre likely found her sittings long and dull, for Cassatt would have staged this scene in her studio, and evidently took great pains with it, making multiple revisions to the headlamp, coachman, and spokes of the wheel.

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Purchased with the

W. P. Wilstach Fund, 1921 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Driving, 1881

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

The Child's Bath, 1880

Oil on canvas

The comparatively simple, practical clothing of the woman depicted here suggests she may be a nurse or paid caregiver. Cassatt obscures her face, focusing instead on the child's loose-limbed posture, but the woman's reddened hand at far left is a calculated focal point. In contrast to the agitated brushwork on the rest of the canvas, the rich color and crisp contours used to evoke this hand draw attention to the artistic and domestic labor that animate this painting.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Mrs. Fred Hathaway Bixby Bequest |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

The Child's Bath, 1880

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

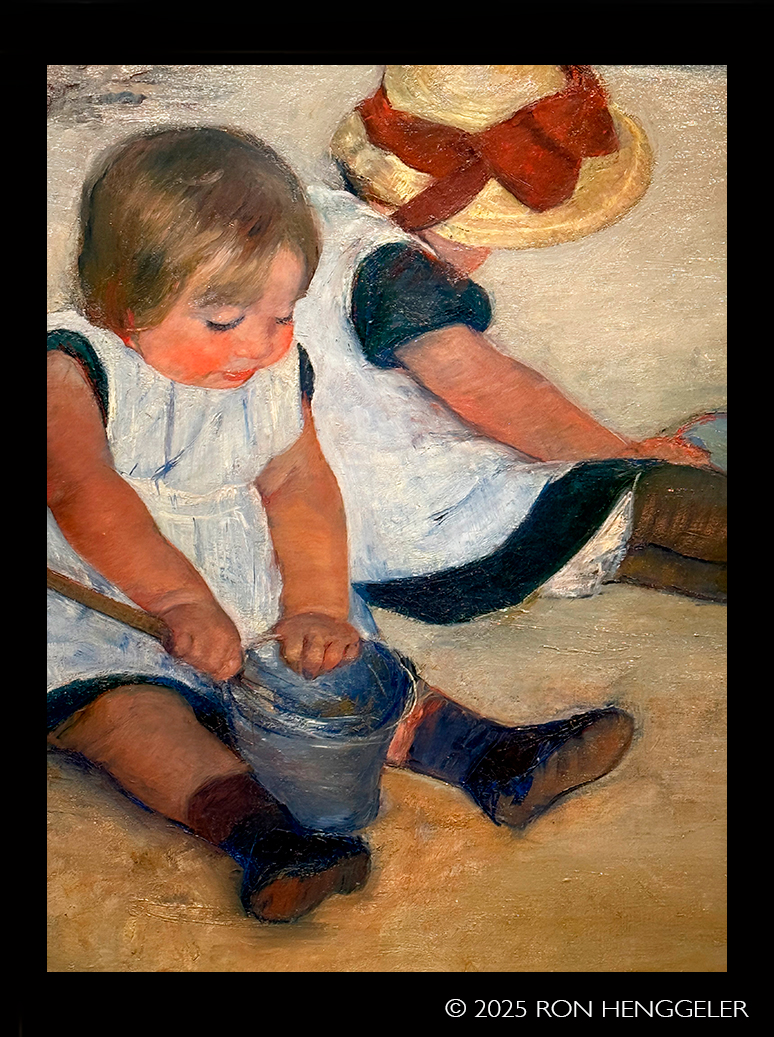

Detail of:

Children Playing on the Beach,

1884-1885

Oil on canvas

Just as Cassatt's adult models often appear engrossed in various forms of work, these two little girls-or, perhaps more accurately, this one little girl, painted twice-appear engrossed in play. Cassatt's studio was filled with toys, and her keen observation of her young models here results in a startlingly accurate portrayal of toddler hands gripping a shovel and a bucket.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Ailsa Mellon

Bruce Collection, 1970.17.19 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Lydia Seated on a Porch, Crocheting, 1881-1882

Oil and tempera on canvas

Like her older sister Lydia, pictured here, Cassatt never married and had no children. In an age when professional ambition and family life were generally considered incompatible for bourgeois women, Cassatt's images of children are, in a sense, brought to us by the fact that she herself did not bear children. The artist was, however, a devoted caregiver to her aging parents and to Lydia herself.

Diagnosed in 1879 with Bright's disease, a degenerative kidney condition, Lydia passed many of her domestic responsibilities to Cassatt, who cared for her older sister until her death in 1882.

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Donated by James W. McGlothlin as part of the James W. and Frances Gibson McGlothlin Collection of American Art, 2022.171 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Lydia Seated on a Porch, Crocheting, 1881-1882

Oil and tempera on canvas

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Woman at Her Toilette, ca. 1880

Oil on canvas

x

Closely related to the color print Woman Bathing, of which three states appear nearby, this freely brushed painting may predate that work by more than a decade. A stamp on the reverse indicates that Cassatt purchased the canvas from an artist's supply store called Rey et Cie between 1877 and 1880, when the shop was located at

51, rue de la Rochefoucauld in Paris. The canvas support for the pastel At the Theater, shown in the 1879 Impressionist exhibition, came from the same shop.

Private collection in memory of Augustine F. Falcione |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Woman at Her Toilette, ca. 1880

Oil on canvas

x |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

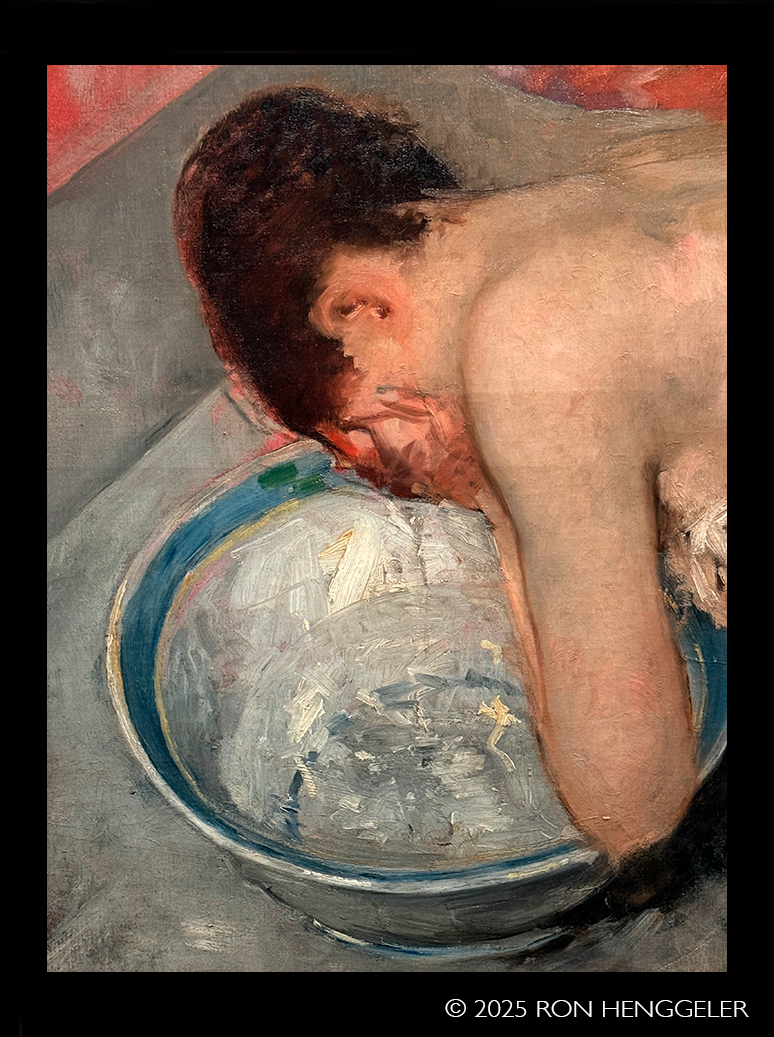

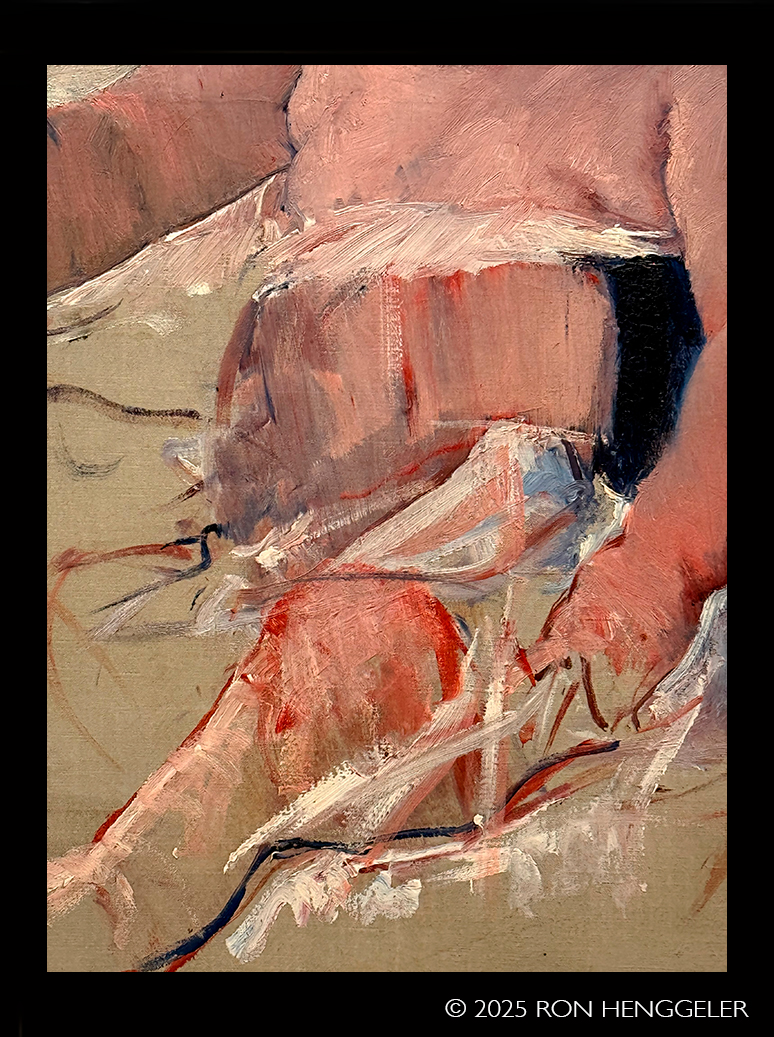

Bathing the Young Heir, 1890-1891

Oil on canvas

A woman dips her hand into a basin, preparing to bathe her plump, rosy charge. The adult model and-most especially-the baby are rendered in naturalistic detail, but the lower half of the composition dissolves into loose, scattered strokes.

The lower left corner is bare of paint. Cassatt likely began this picture around the time she created her drypoint series and "Set of Ten" but abandoned it unfinished. In the early twentieth century, she returned to some of her previously unfinished canvases, deeming them finished after all, and signing each in a broad hand with black paint.

Private collection, courtesy of Waqas Wajahat, New York |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Bathing the Young Heir, 1890-1891

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Woman in a Black Hat and a Raspberry Pink Costume, ca. 1905

Pastel on paper

Collection of Robbi and Bruce Toll

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Woman in a Black Hat and a Raspberry Pink Costume, ca. 1905

Pastel on paper |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

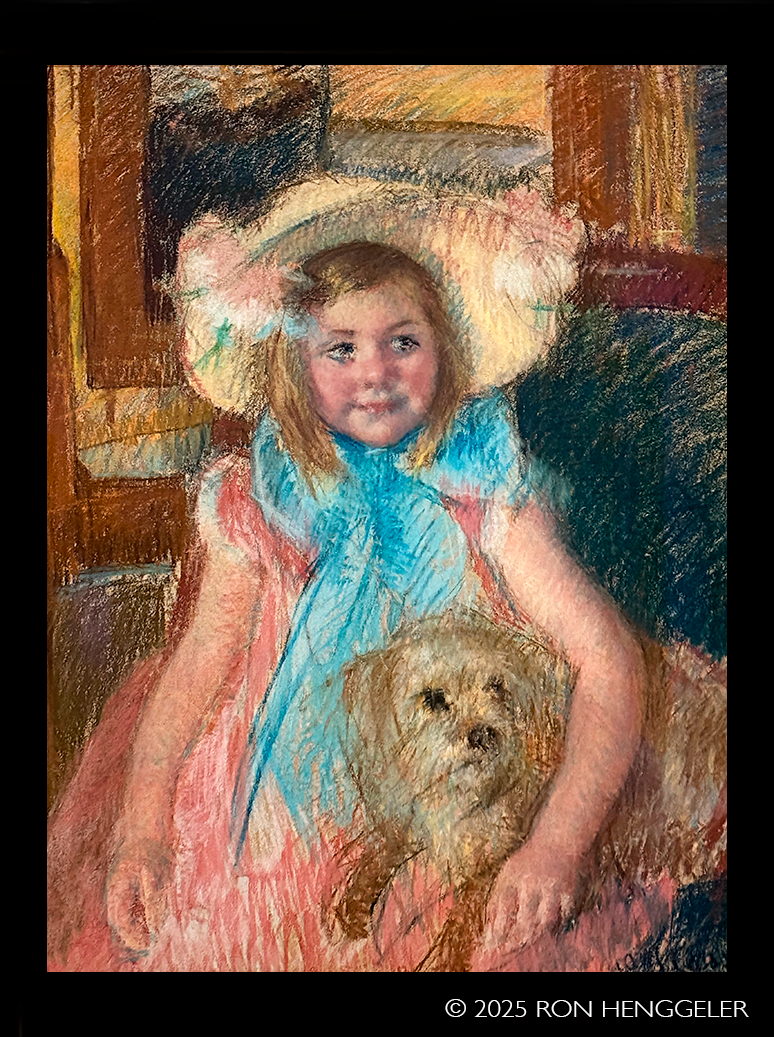

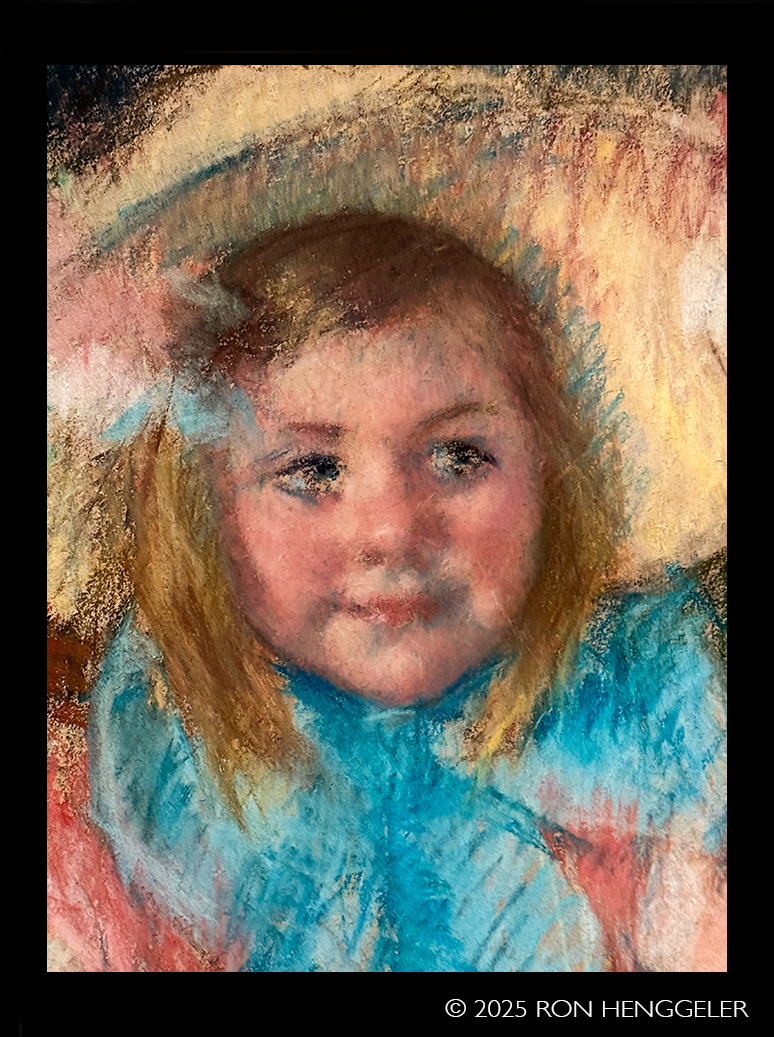

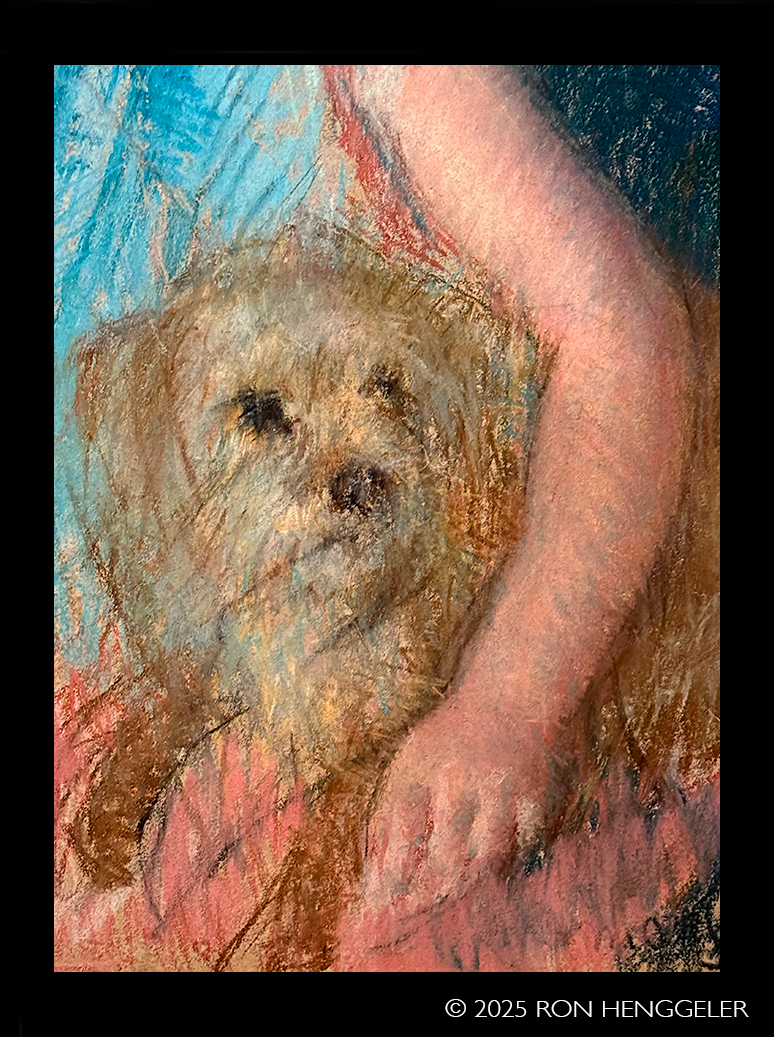

Sara in a Large Flowered Hat, Holding Her Dog, ca. 1901

Pastel on paper

Like many of Cassatt's pastels, this one exhibits a tension between carefully finished, highly naturalistic passages-notably the sweet face of this favored model-and freer, more rapidly rendered areas, where we seem to watch the artist's hand move across the sheet of paper, as in the dog, the hat, the great blue bow. Cassatt seems to have developed this approach in her pastel practice but eventually brought it to bear on her oil paintings and even her prints, letting the juxtaposition of tight and loose handling call attention to her process and underscore her virtuosic skill.

Collection of Mrs. Diane B. Wilsey |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Sara in a Large Flowered Hat, Holding Her Dog, ca. 1901

Pastel on paper |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Sara in a Large Flowered Hat, Holding Her Dog, ca. 1901

Pastel on paper |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Sara in a Large Flowered Hat, Holding Her Dog, ca. 1901

Pastel on paper |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Clarissa, Turned Right, with Her Hand to Her Ear, 1890-1893

Pastel on paper

Drs. Tobia and Morton Mower

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Clarissa, Turned Right, with Her Hand to Her Ear, 1890-1893

Pastel on paper |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Woman Arranging Her Veil, ca. 1890

Pastel on wove paper

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Bequest of Lisa Norris Elkins, 1950

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

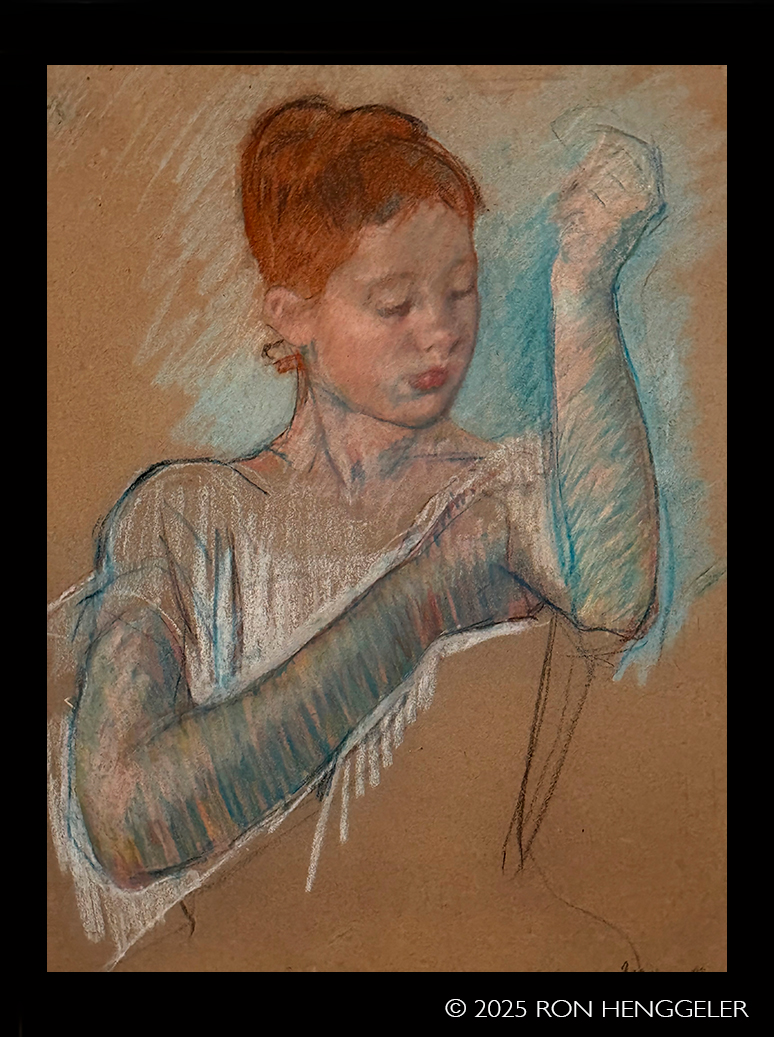

FINISHED UNFINISHED

The successive states of Cassatt's color prints testify to both the artist's restless experimentation and her desire to document that experimen-tation, preserving the process as well as the finished product. A related interest in laying process bare emerges in pastels and paintings that exhibit a tension between tightly rendered, highly finished passages and areas of looser, more open facture. Solid heads and bodies give way to slashing strokes of color and even blank stretches of canvas or paper along the edges of Cassatt's compositions, as her designs dissolve into their constituent marks and materials. Such works seem to invite us to observe their making, allowing us essentially to eavesdrop on the artist as she applies hatches of pastel and strokes of paint.

Of course, Cassatt also abandoned some works unfinished. In many cases signatures provide the clearest indication as to whether-and when-she considered her work complete. She signed some sketch-like pastels at the time of their making, before exhibiting, selling, or giving them away. Other unresolved works bear large, black, blurry signatures, applied near the end of her life, with failing eyesight and deteriorating handwriting, as she reappraised her earlier production.

Still others are unsigned, retained in her studio or by her family and never intended for public display. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

The Long Gloves, 1886

Pastel on blue gray paper discolored to brown Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, gift of an anonymous donor in celebration of the Legion of Honor Centennial |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

The Long Gloves, 1886

Pastel on blue gray paper discolored to brown |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

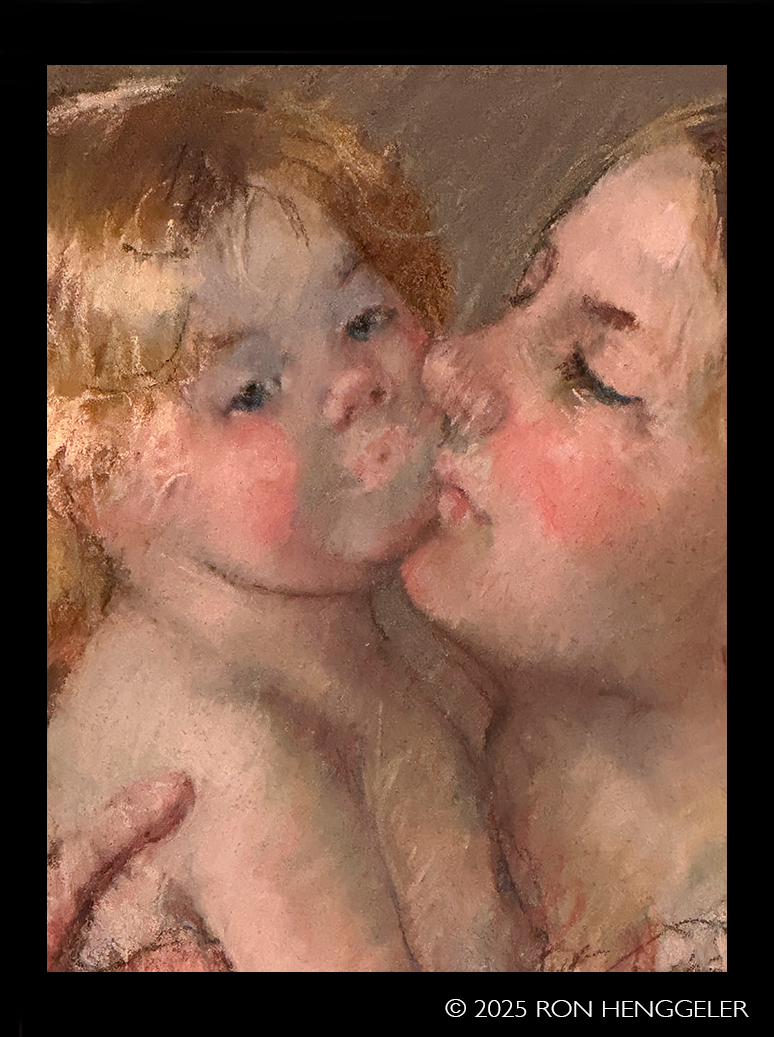

A Kiss for Baby Ann, No. 3, 1897

Pastel on paper

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, gift of an anonymous donor in celebration of the Legion of Honor Centennial

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

A Kiss for Baby Ann, No. 3, 1897

Pastel on paper |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

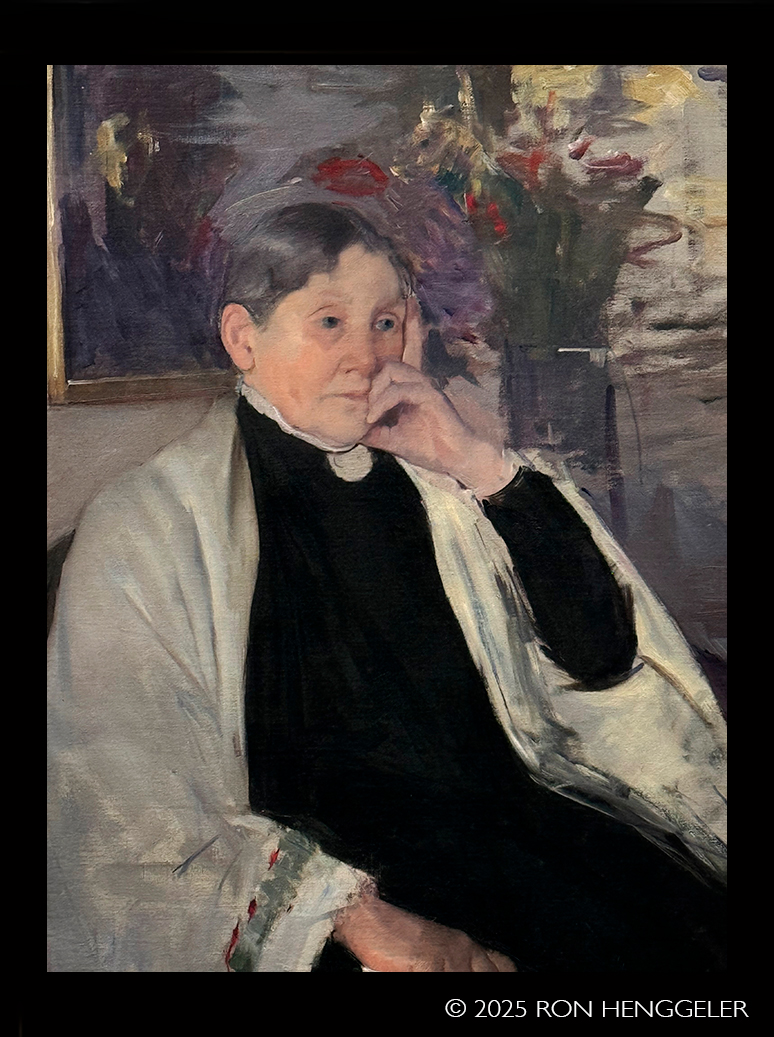

Portrait of Mrs. Robert S. Cassatt, the Artist's Mother, ca. 1885

Oil on canvas

Cassatt lived with her parents in France for nearly twenty years. By the early 1880s, her mother's declining health often required Cassatt to set art-making aside and serve as a caregiver. Writing to her brother in late 1883, the artist remarked, "I have not touched a brush... have not been out of Mother's room except for a walk.... It will do me good to get to work again." Mrs. Cassatt posed for this portrait at about seventy-three years old. Its open, unpainted corners contrast with the high finish of the sitter's face and hands, intimately familiar and rendered with evident care.

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, William H. Noble Bequest Fund, 1979.35 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Portrait of Mrs. Robert S. Cassatt, the Artist's Mother, ca. 1885

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

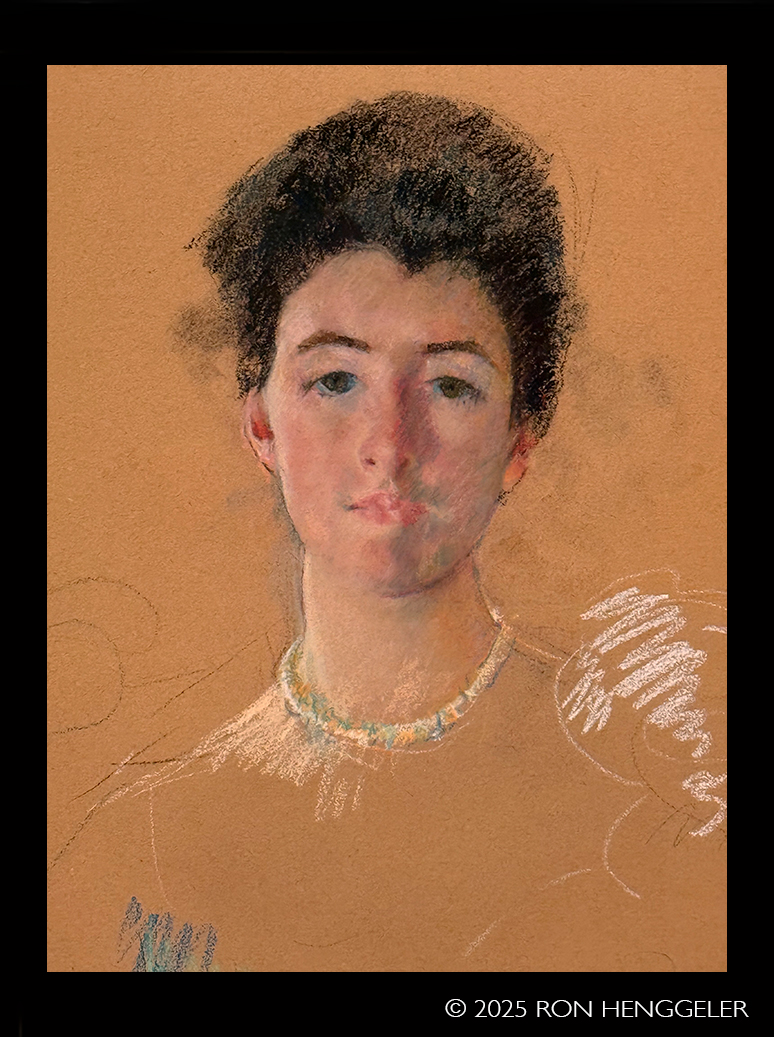

Portrait of Mabel S. Simpkins (later Mrs. George Russell Agassiz),

1898

Pastel on wove paper

Though it might appear to be a preparatory sketch, this pastel was in fact a formal commission, completed over a few days when Cassatt was visiting Boston from Paris on a North American tour designed to enhance her reputation and drive up sales. While the sitter's face is carefully drawn, loose flourishes hint at her puffed sleeves. A burst of blue at her breast looks very like a media test.

Cassatt's signature at lower right confirms that she considered this work finished.

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Frances and Bayard Storey, 2017 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Sketch for "Françoise in a

Round-Backed Chair, Reading," 1909

Oil on canvas

Private collection, courtesy of Waqas Wajahat, New York

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Sketch for "Françoise in a

Round-Backed Chair, Reading," 1909

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

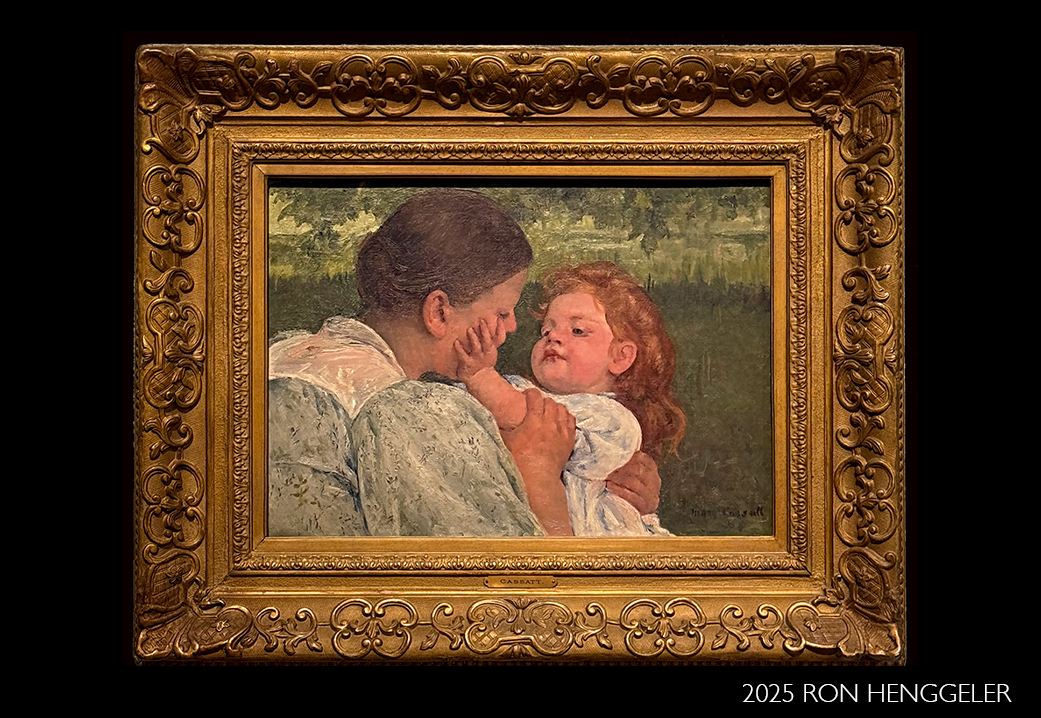

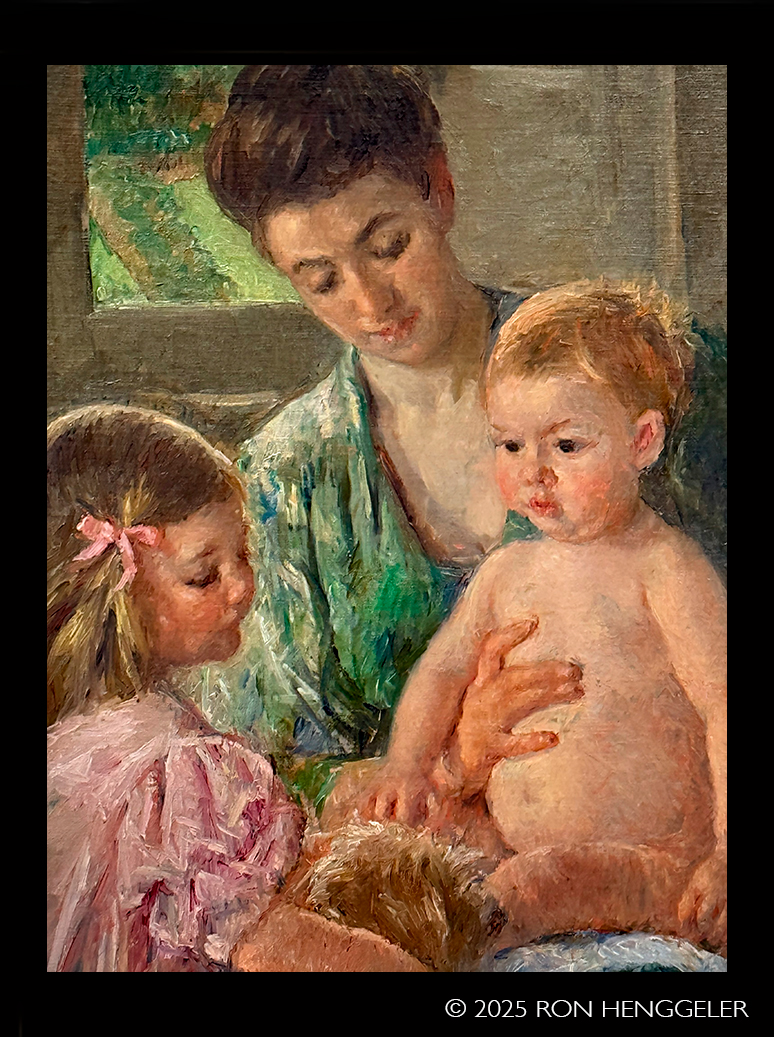

The Family, 1893

Oil on canvas

Eighteen ninety-three was a momentous year for Cassatt. In Chicago, her first public commission-a monumental mural (today lost) -appeared at the Women's Building of the World's Columbian Exposition. In Paris, the Durand-Ruel Gallery mounted Cassatt's first monographic exhibition-comprising forty-seven pastels, prints, and paint-ings, among them this canvas. Its composition, featuring a young woman with an infant perched on her lap and a second child looking on at left, draws inspiration from Renaissance depictions of the Madonna and Child with the infant Saint John the Baptist.

Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., 71.498 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

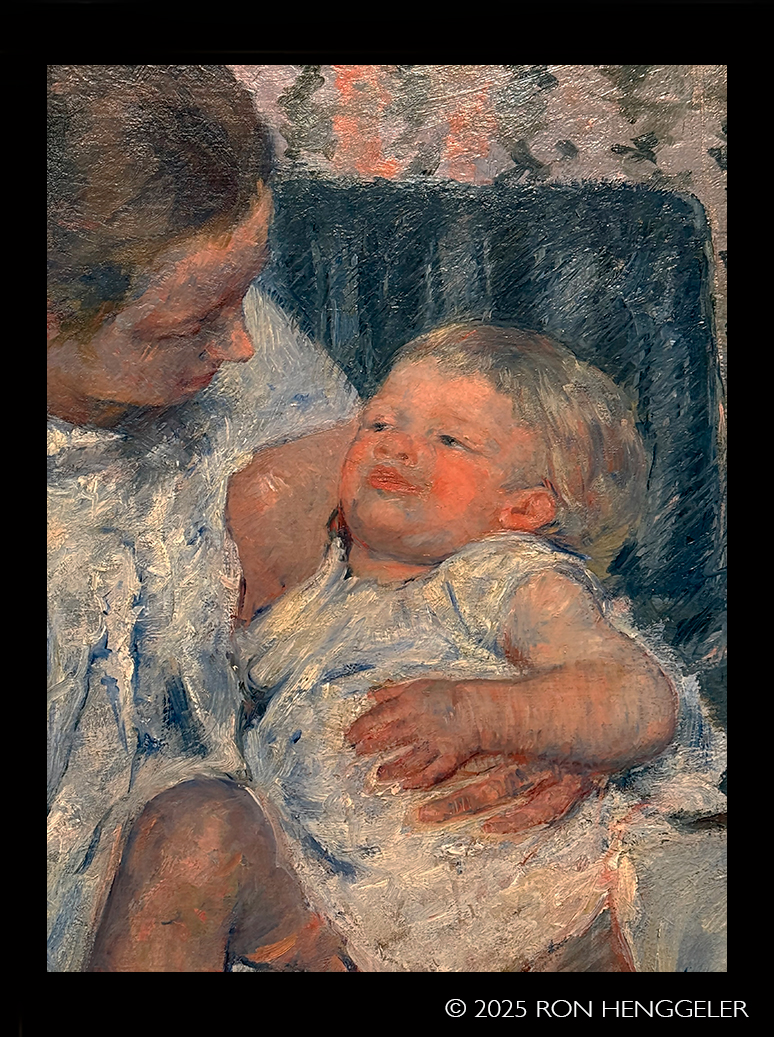

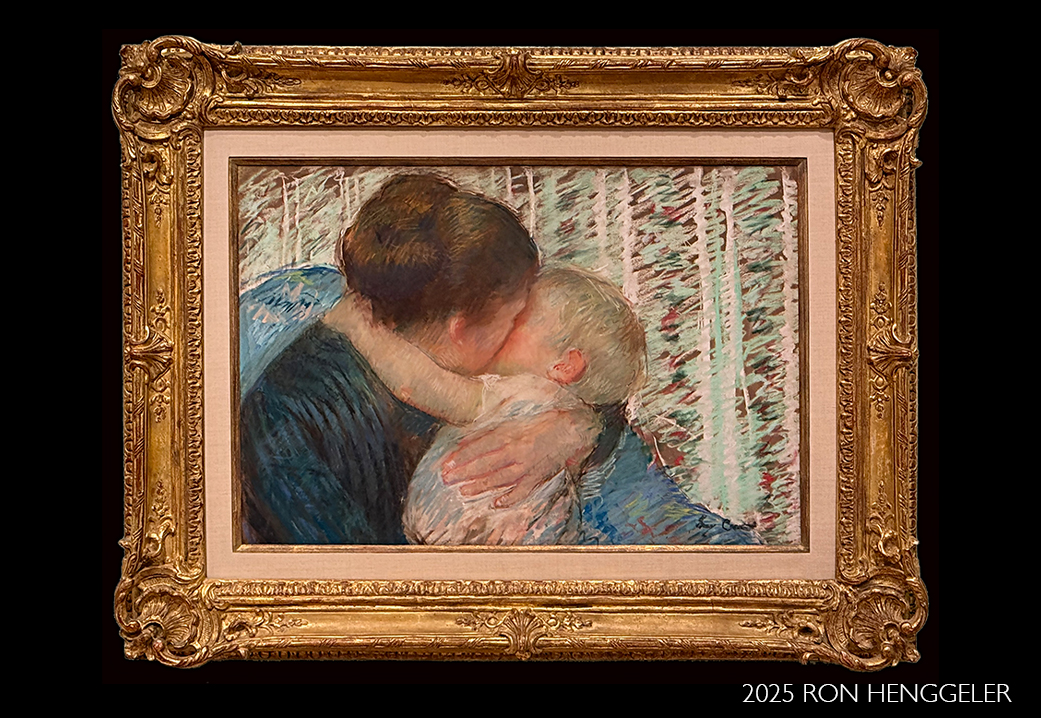

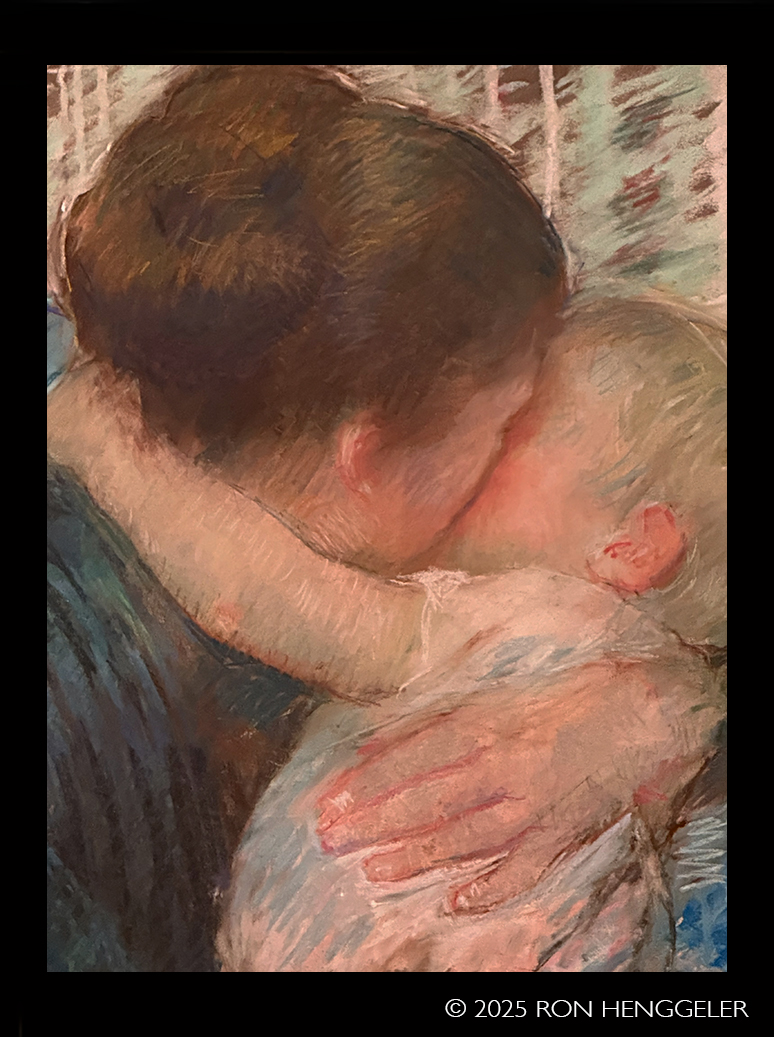

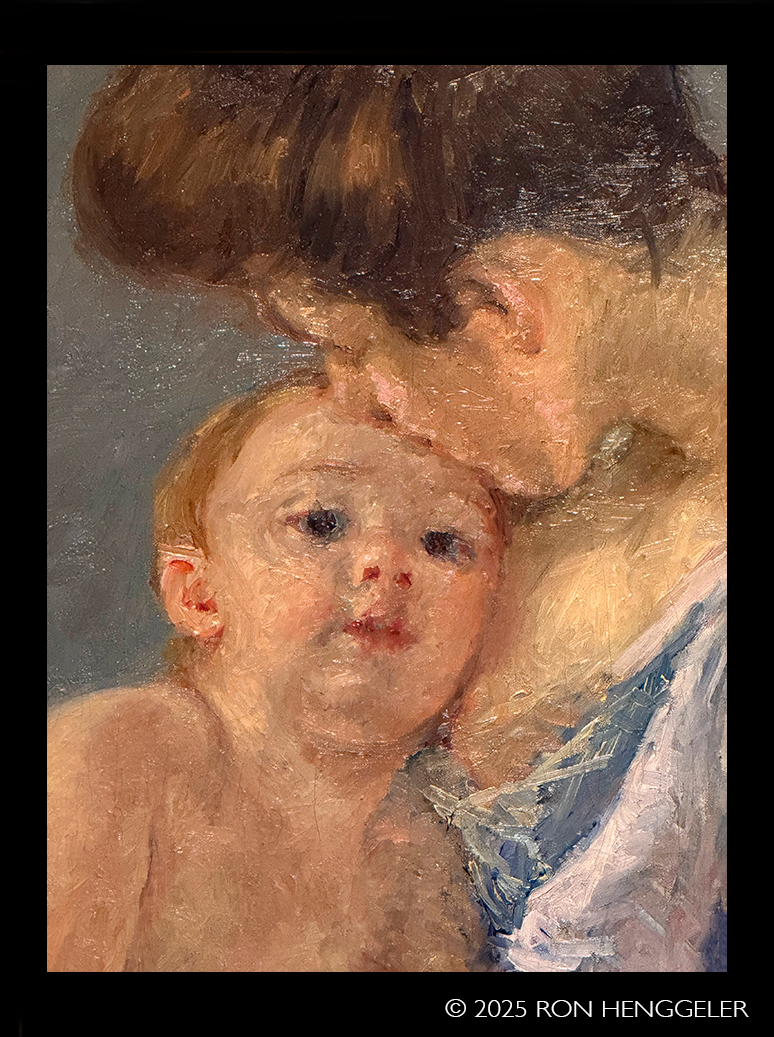

Maternity

(Mother Kissing Her Baby), 1906

Oil on canvas

Lively brushwork and a shimmering palette evoke a tender moment-perhaps post-bath and pre-bedtime-when a woman plants a kiss on her baby's forehead. Drawing on the long tradition of Madonna and Child imagery, Cassatt used gesture, movement, and touch to update the theme, presenting child-rearing as a physically and emotionally engaging occupation for the modern woman.

Collection of Mrs. Diane B. Wilsey |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

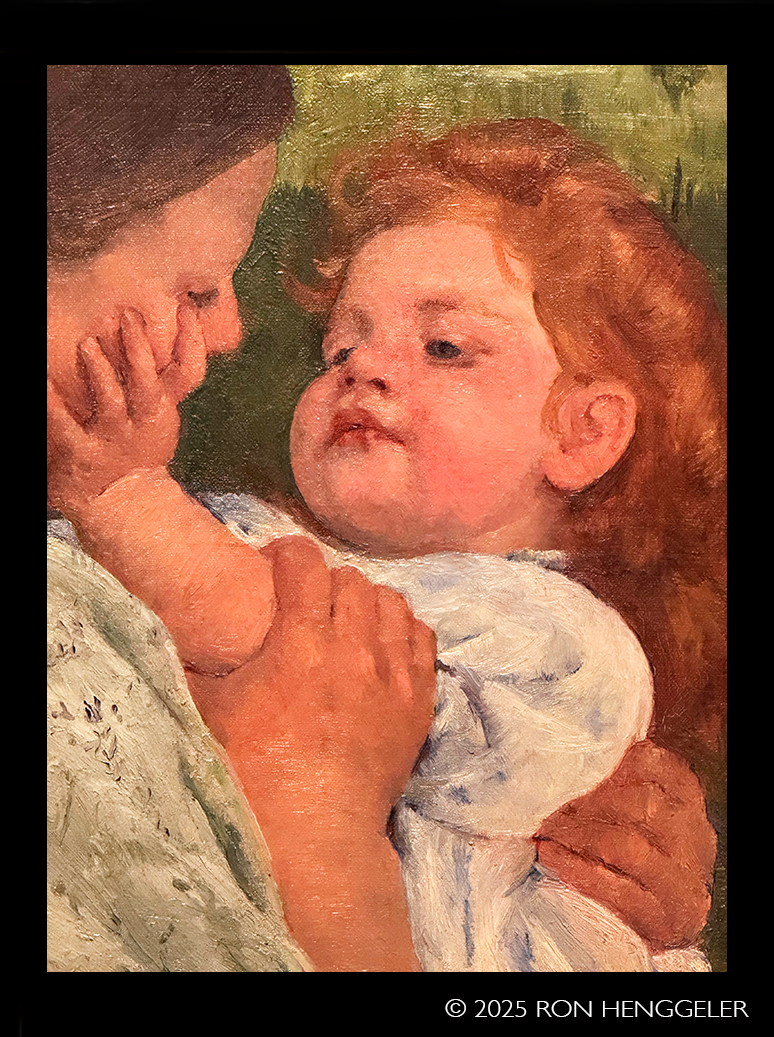

Detail of:

Maternity

(Mother Kissing Her Baby), 1906

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

THE "MODERN MADONNA"

During the final decade and a half of Cassatt's career, she focused with increasing single-mindedness on images of women and children. She was content to see these works exhibited and sold as pictures of mothers and children, but, considered on the more literal level of studio practice, they are more complicated. The women who appear in them were seldom the mothers of the children in their arms. While Cassatt's juvenile models were often the children of friends and family members, her adult models were generally domestic employees who worked for the artist or her friends; she paid them to pose. Though Cassatt often dressed these models up as bourgeois ladies, work-reddened hands sometimes give their class status away, reminding us that Cassatt's pictures do not offer an artless record of her own experience but, rather, an array of carefully crafted studio fictions.

Mother-and-child imagery helped Cassatt establish a conversation with Old Master precedents, specifically religious images of the Madonna and Christ Child painted and sculpted by Italian Renaissance masters.

But Cassatt's ability to wring endlessly varied compositions from this theme also ties her late work to that of her fellow Impressionists Claude Monet and Paul Cézanne. Their pictures of water lilies and apples, respectively, treat the same subjects again and again. But those subjects, unlike Cassatt's, do not carry gendered meaning and have not led the men who chose them to be written off as sentimental. Taking Cassatt's late exploration of the "mother-and-child" theme seriously as a formal matter grants us access to the infinite possibilities she discovered in her great subject: children and the work of caring for them. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

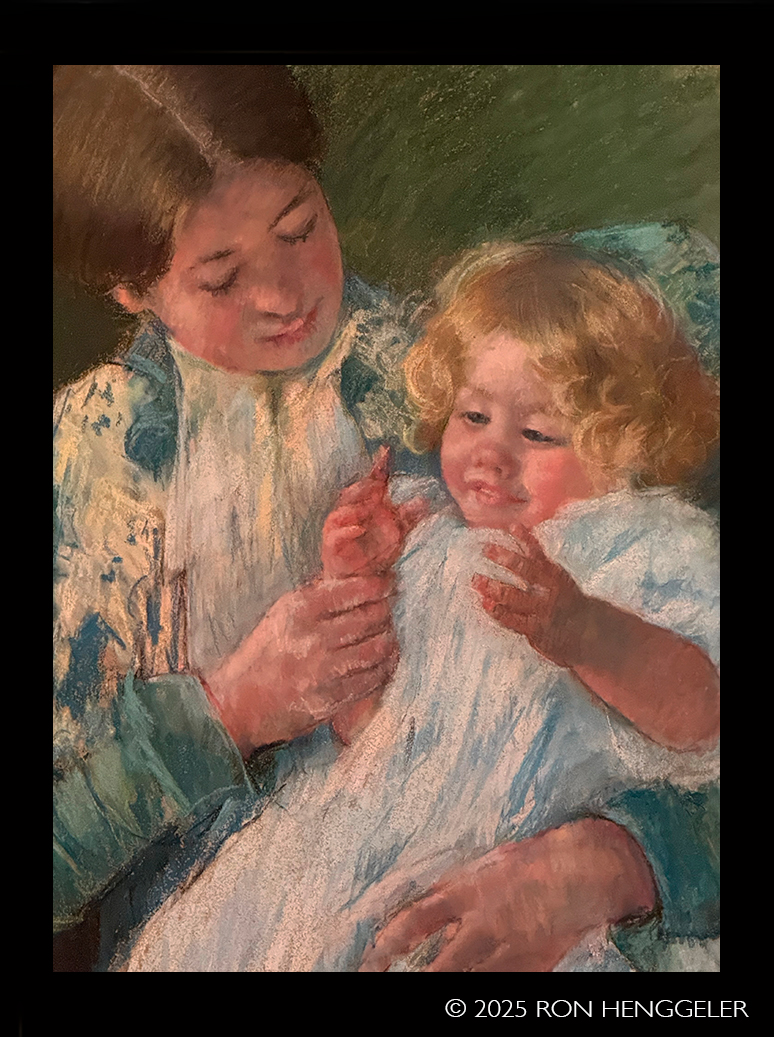

Pattycake (Mother and Child), 1897

Pastel on paper

Denver Art Museum, Anonymous bequest, 1986.729

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Pattycake (Mother and Child), 1897

Pastel on paper |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

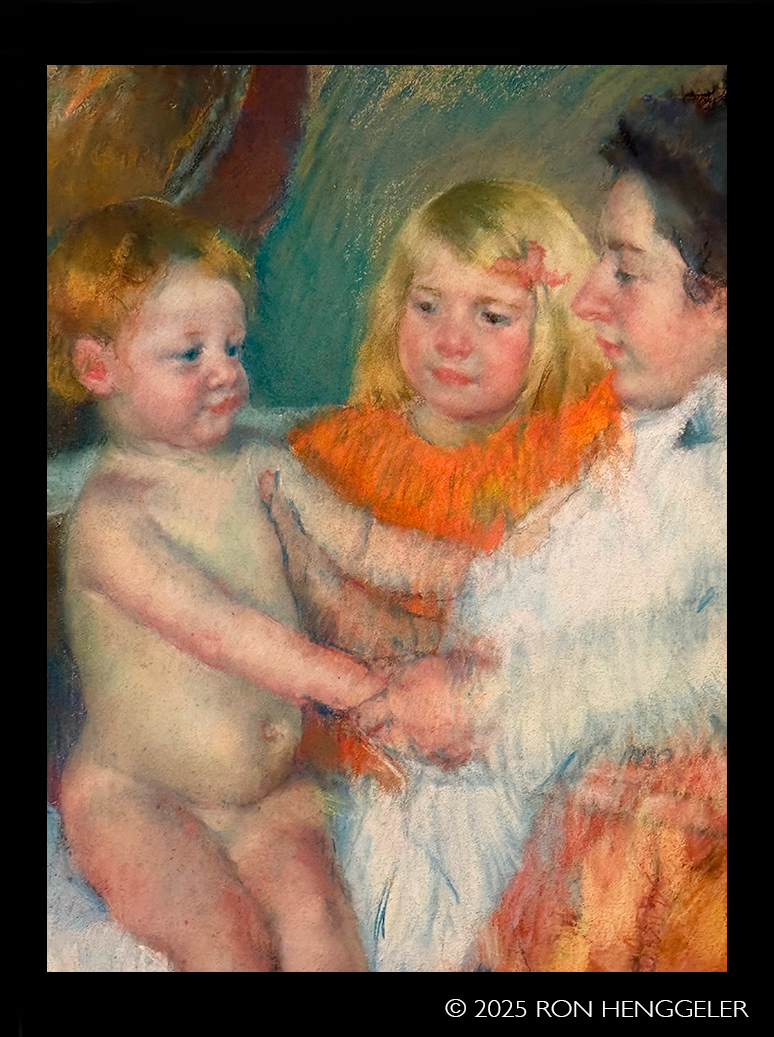

Mother, Sara, and the Baby, 1901

Pastel on paper

Drs. Tobia and Morton Mower

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Deatil of:

Mother, Sara, and the Baby, 1901

Pastel on paper |

|

| |

|

|

|

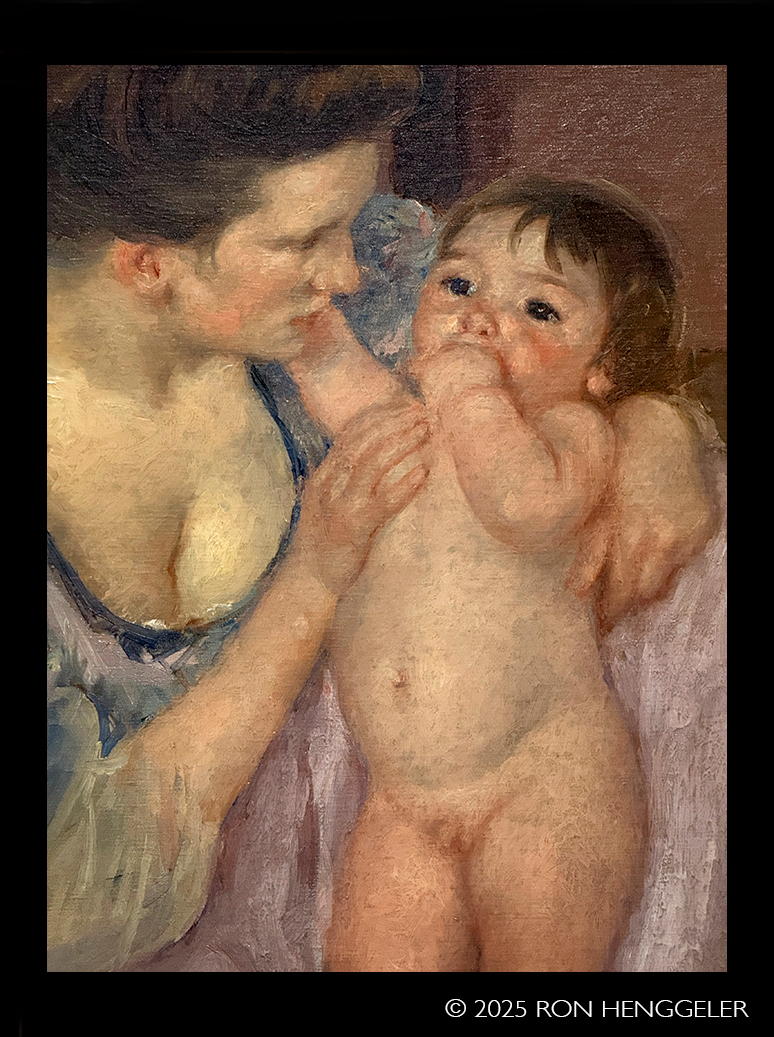

| |

Detail of:

Mother and Child, 1905

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

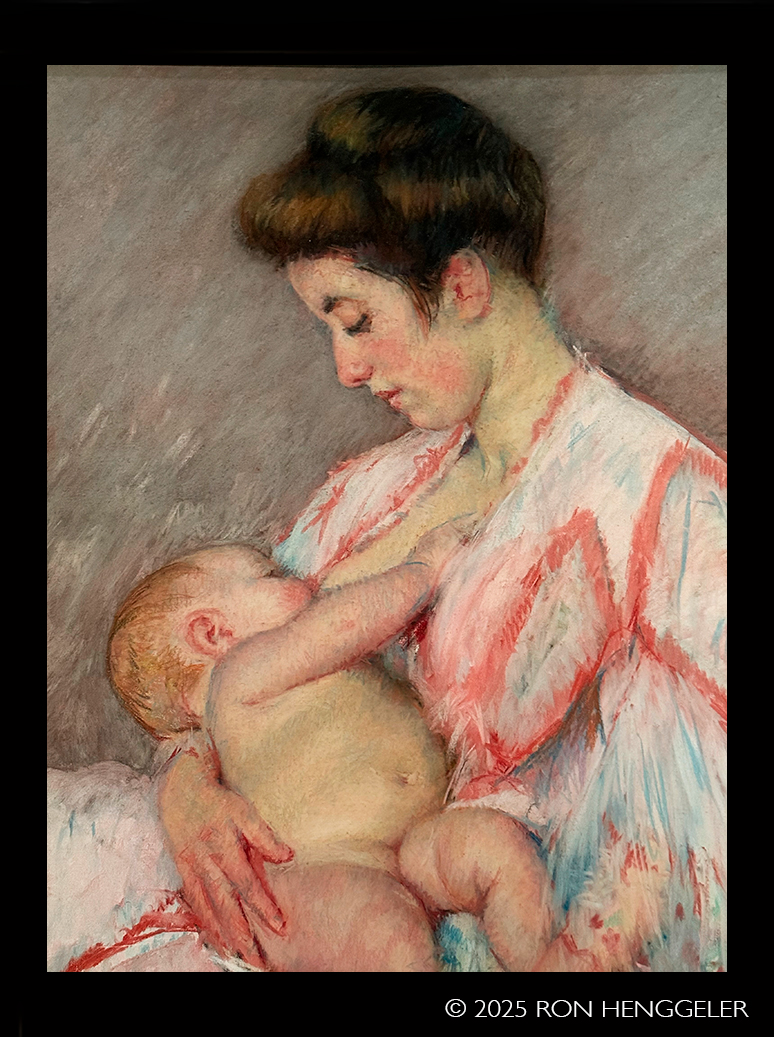

Baby John Nursing, ca. 1908

Pastel on canvas

Private collection of Keith and Melissa Meister

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Baby John Nursing, ca. 1908

Pastel on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Maternal Caress, 1896

Oil on canvas

Cassatt wrote of this picture to her art dealer: "I was extremely persistent with this, perhaps too much, but I only finished it on Saturday,... I am counting on it improving as it settles." What she meant by "persistent" is not clear, though she may have been referring to the lively application of different green paints, or the textured patterning on the woman's sleeve made while the paint was still wet, or the pains she took to capture a child's determined exploration of an adult face-and the adult's patient, restraining hand.

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Bequest of Aaron E. Carpenter, 1970 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Maternal Caress, 1896

Oil on canvas

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Children Playing with a Dog, 1907

Oil on canvas

Private collection, United States

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Children Playing with a Dog, 1907

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

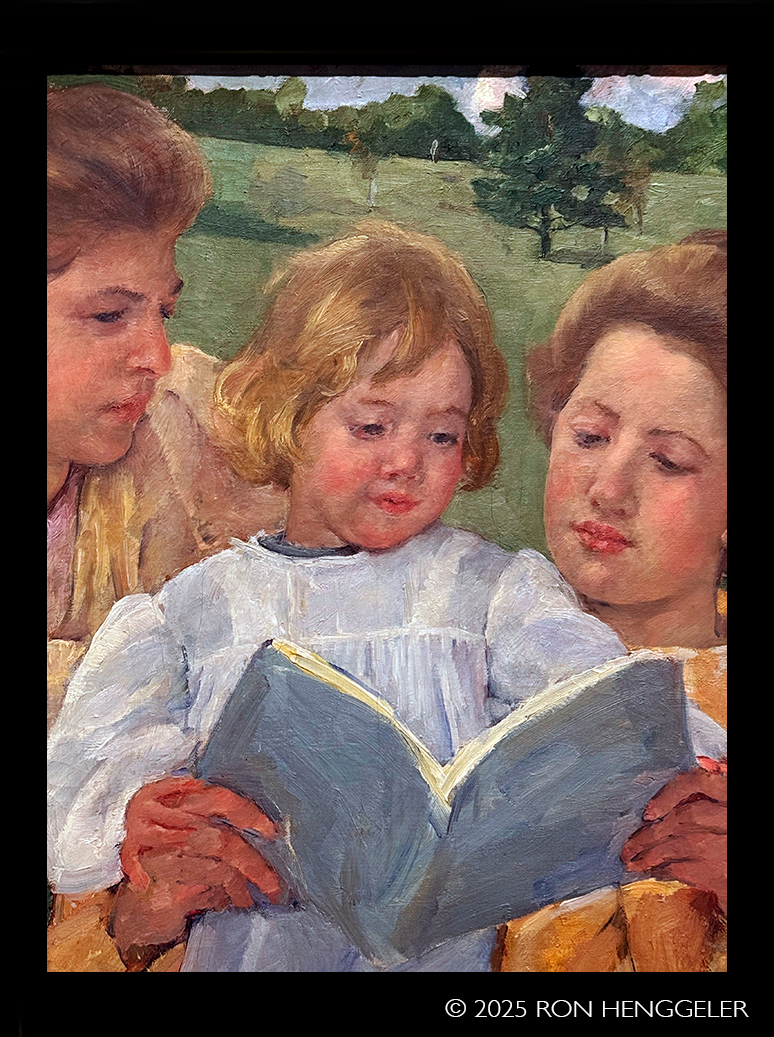

Mother and Two Children, ca. 1905

Oil on canvas

The Westmoreland Museum of American Art, Greensburg, Pennsylvania, Anonymous gift, 1979.1 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of:

Mother and Two Children, ca. 1905

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Mother and Child, 1905

Oil on canvas

Following on the success of her mural at the Women's Building of the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Cassatt created these paintings for the ceiling of the Ladies' Reception Room at the lieutenant governor's office in the Pennsylvania State Capitol. Their circular format echoes the shape of celebrated Madonnas by Botticelli and Raphael, although Cassatt's scenes of motherhood are resolutely modern, featuring fashionably dressed women engaged in intimate, informal interactions with children. Cassatt ultimately withdrew from the commission; the paintings were never installed in the Capitol.

Private collection |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Marcellin Desboutin

(1823-1902)

The Printer Leroy, 1875

Drypoint on laid paper

Cassatt relied on the professional printer Modeste Leroy, pictured here in a portrait by another print-maker, Marcellin Desboutin, to help handle the intricate process of creating her "Set of Ten." While Cassatt conceived and designed the comp-ositions, Leroy handled the complex choreography of preparing and aligning the multiple printing plates required to produce each scene's colors, patterns, and linework. Along the lower edge in many of the finished prints, in an unusual gesture of acknowledgement, Cassatt inscribed Leroy's name in graphite alongside her own.

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

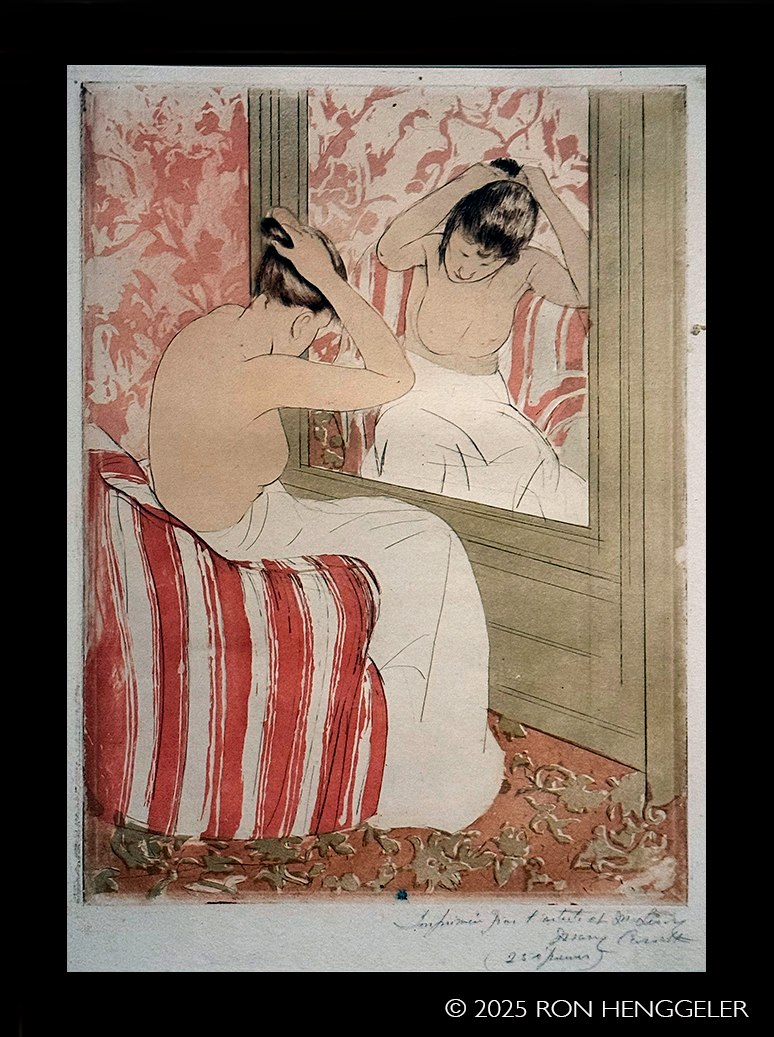

PRINTING IN COLOR

In 1890, Cassatt attended an exhibition of Japanese art in Paris.

Captivated by the bright colors, dynamic patterns, and everyday scenes in Japanese woodblock prints, she came away determined to reverse-engineer these effects in a Western-style intaglio print, writing to her friend and fellow Impressionist Berthe Morisot, "You couldn't dream of anything more beautiful. I dream of it and nothing else but color on copper." The next winter, she embarked on a series of color prints now known as the "Set of Ten." These draw inspiration from Japanese precedents to portray the private lives of modern Parisian women: bedtime and toilette rituals, the bathing of a child, the drinking of tea, the sealing of a letter, a dress fitting, a bus ride, a quiet moment at a party.

Working in her studio with the master printer Modeste Leroy, Cassatt invented a new method of printing in color. She later downplayed the intricacy of the process, explaining, "My method is very simple. I drew an outline in dry point and transferred this to the two other plates, making in all, three plates, never more for each proof-Then I put the aquatint wherever the color was to be printed; the color was painted on the plate as it was to appear in the proof." A dozen states of the first print in the series, shown here, tell a more complicated story.

Capturing their process of trial and error in intermediate proof impres-sions, Cassatt and Leroy puzzled out the printing of a single image from multiple copper plates using a range of intaglio techniques. Once Cassatt was satisfied with an image, she and Leroy would pull twenty-five impressions of the final state. As Cassatt confided to a friend at the time, "The printing is a great work; sometimes we worked all day (eight hours) both, as hard as we could work & only printed eight or ten proofs in the day." The results are among the most inventive and technically daring works in the history of modern printmaking. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

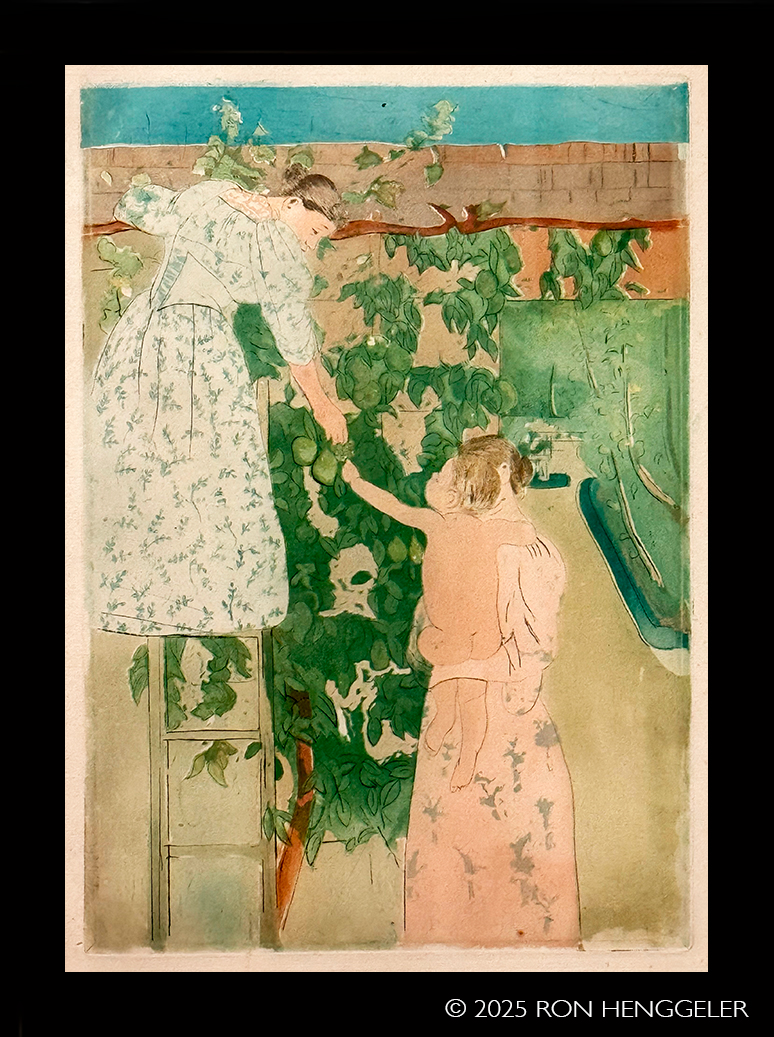

Gathering Fruit, 1893

Color drypoint, soft-ground etching, and aquatint on paper, state 8-9 of 11

For the Chicago World's Fair in 1893, Cassatt was commissioned to create a mural on the theme of Modern Woman. This drawing and print are based on the central panel of that mural (today lost), where women and girls gathered to harvest fruit, recasting the story of Eve plucking fruit from the Tree of Knowledge as an allegory of female emancipation through collective effort.

Cohn Family Collection |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

The Coiffure, 1890-1891

Color drypoint and aquatint on laid paper, state 5 of 5

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC,

Chester Dale Collection, 1963

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

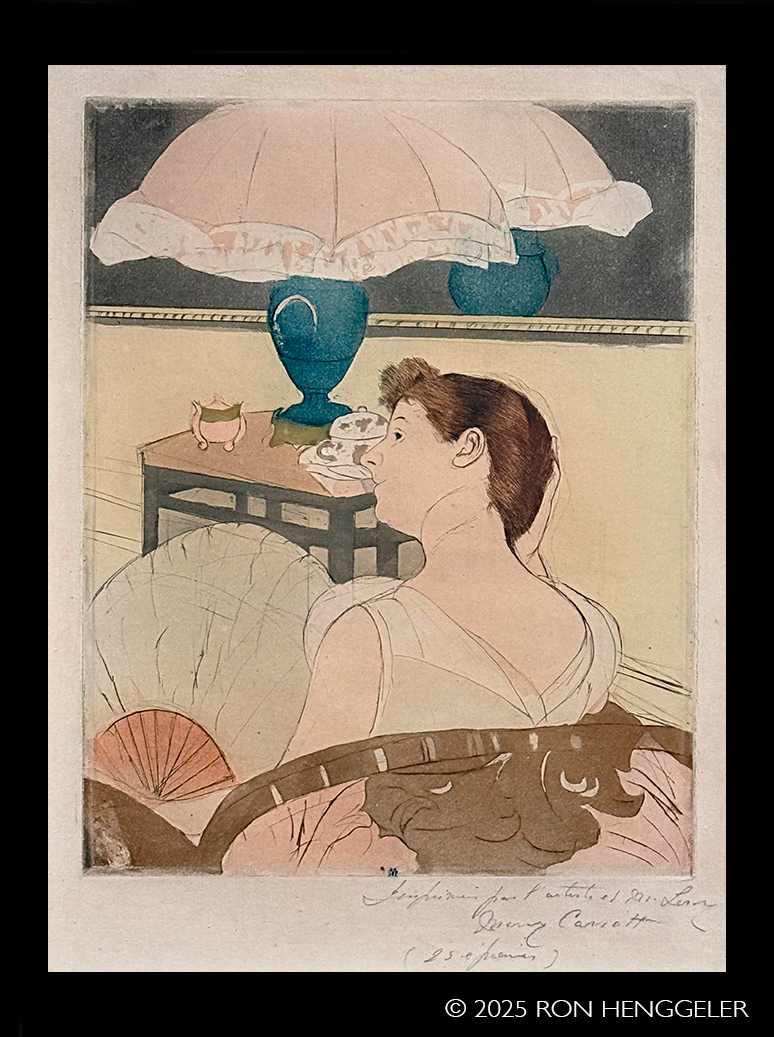

The Lamp, 1890-1891

Drypoint, aquatint, and etching, state 4 of 4

Adelson Galleries, New York

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

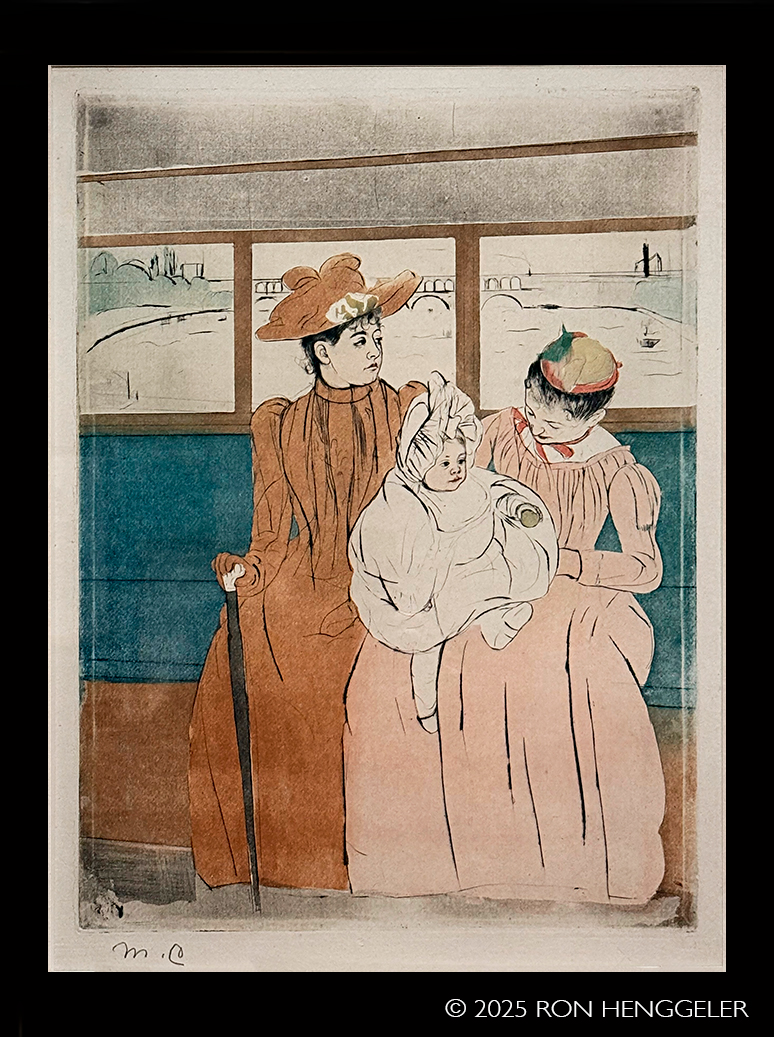

In the Omnibus, 1890-1891

Drypoint and aquatint, printed in colors from three plates, state 5 of 7

Private collection

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Maternal Caress, 1890-1891

Drypoint, aquatint, and etching in colors, on laid paper, state 6 of 6

Promised gift of Rebecca Henderson

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Afternoon Tea Party, 1890-1891

Color aquatint and drypoint on wove paper, state 4 of 4

Private collection

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Mother's Kiss, 1890-1891

Drypoint and aquatint in colors, on laid paper, state 5 of 5

Promised gift of Rebecca Henderson

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

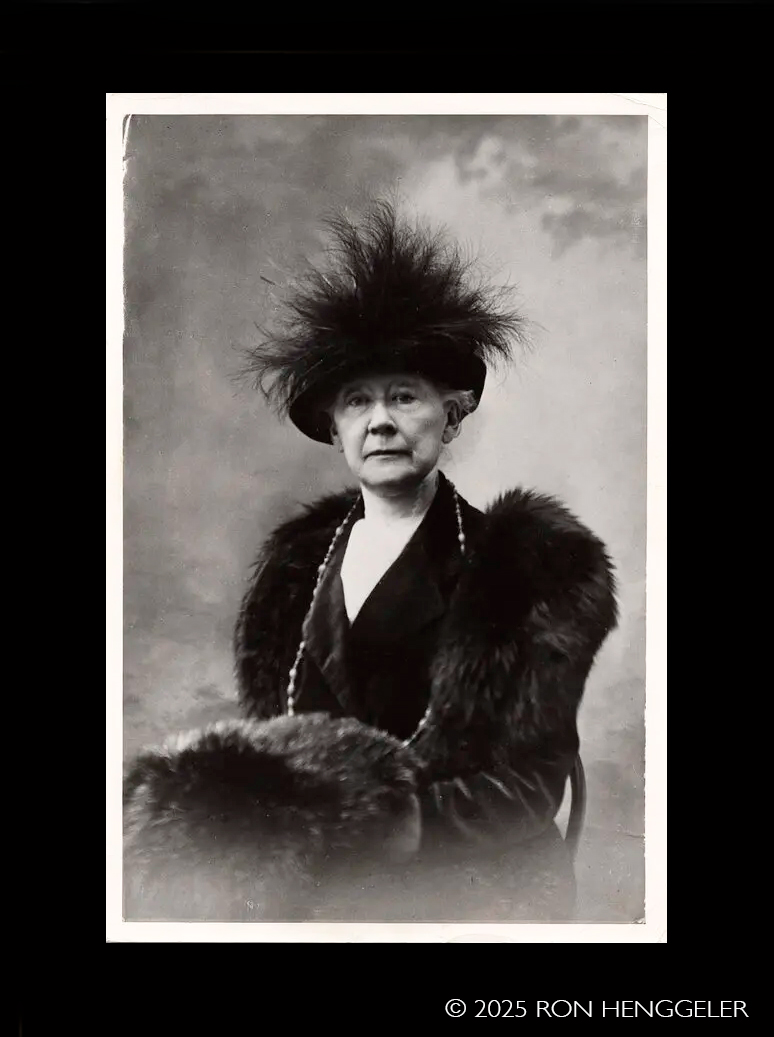

| |

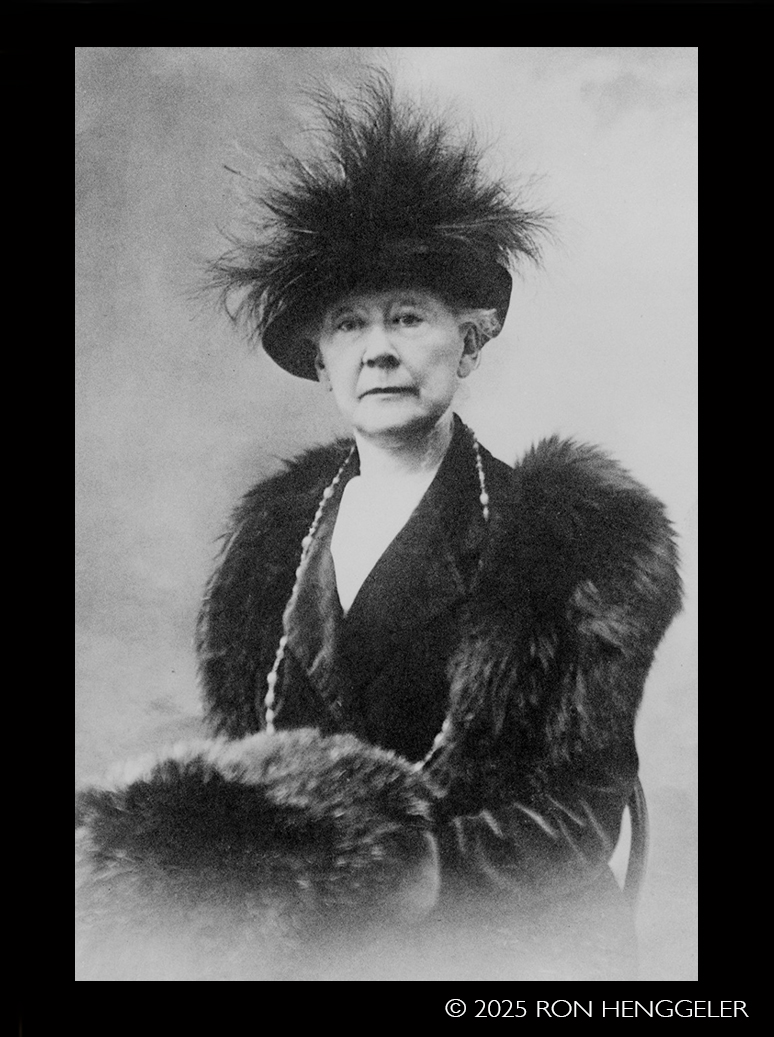

Cassatt did not like to be photo-graphed, but she must have liked this image-in which she wears a hat made by the Paris milliner and fashion designer Caroline Reboux-since she selected it for her American passport. At age sixty-six, Cassatt traveled to Egypt (via Munich, Vienna, Budapest, and Constantinople) with her brother Gardner, sister-in-law Jennie, and nieces Ellen Mary and Eugenia Cassatt. She wrote from Egypt: "Fancy going back to babies & women, to paint.... I am crushed by the strength of this Art." |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

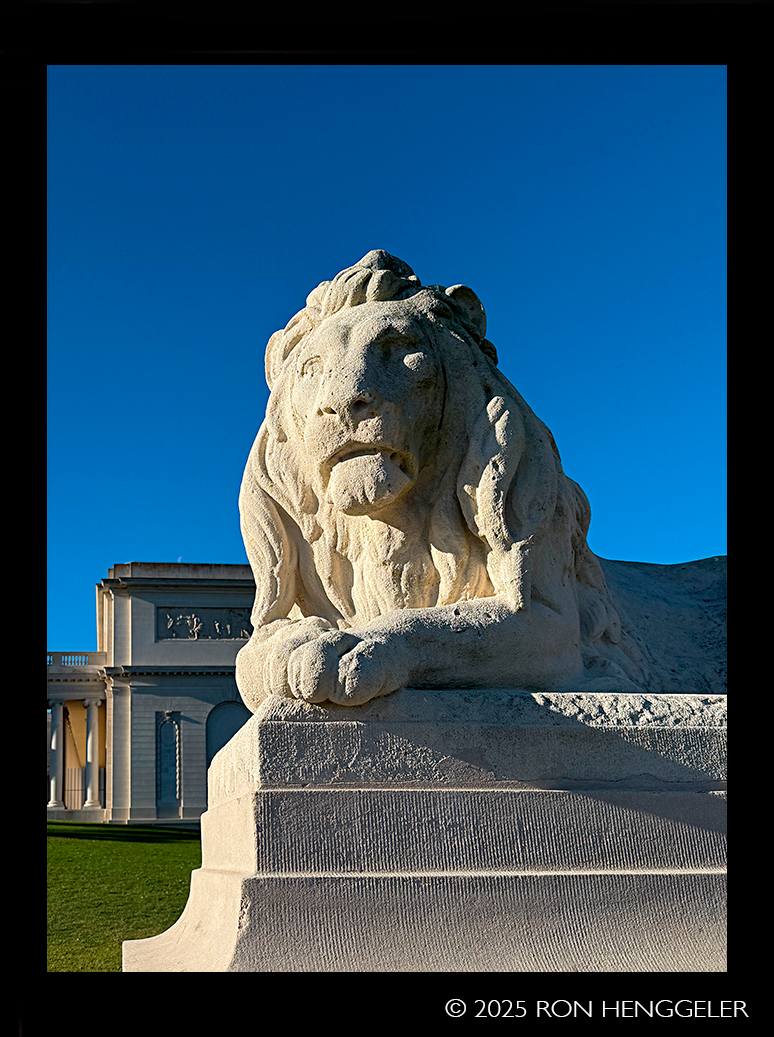

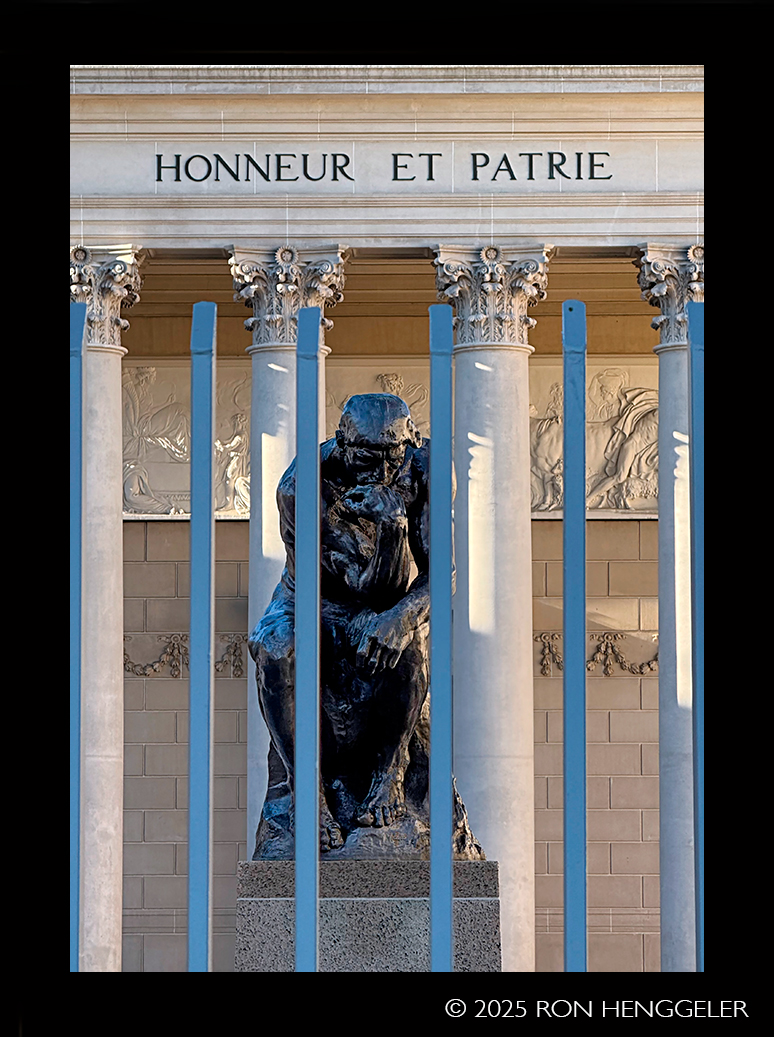

It’s the Legion of Honor’s 100th anniversary! |

|

| |

|

|